|

You and your climbing partner are six pitches up on Goat Wall in Mazama, WA when a sudden lightning storm moves in with heavy rain and lightning. Abandoning the climb you begin to simultaneously rappell off (an advanced—and somewhat risky—climbing technique where two climbers rappel at the same time on the same rope counterbalancing one another). On the last rappell, you neglected to tie a knot on your side of the rope and misjudged the distance to the ground, and rappelled of the end of the rope a few feet above the ground. Unfortunately, your climbing partner, Jessie was roughly 20 feet above you when you fell. With the loss of your counterbalanced weight, the rope pulled through the anchor and Jessie fell to the ground landing on her right side and head in the talus. When you reach her, Jessie is unresponsive and bleeding from her nose and ears; some of the fluid appears to be a light yellow and her helmet is cracked. A quick physical exam reveals a soft spot on her skull behind her right ear and crepitus in multiple ribs on her right side. Her pulse rate is 168 and regular; her respiratory rate is 26 and slightly irregular; her skin is pale. What is wrong with Jessie and what should you do? Click here to find out. Don't know where to begin or what to do? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

0 Comments

You and a few friends just returned from a hot, weekend backpacking trip in the Superstition Mountains outside Phoenix, AZ. It was the first trip for one of his friends, Alan, who is slightly overweight and unfit, had a difficult time with the heat, distance, and elevation changes. Monday morning, the day after the trip, Alan called you complaining of very sore leg and back muscles; he said he could hardly get out of bed and taking 600 mg of ibuprofen didn't help. What do you think might be wrong with Alan, how do you find out, and what should you do? Click here to find out. Don't know where to begin or what to do? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

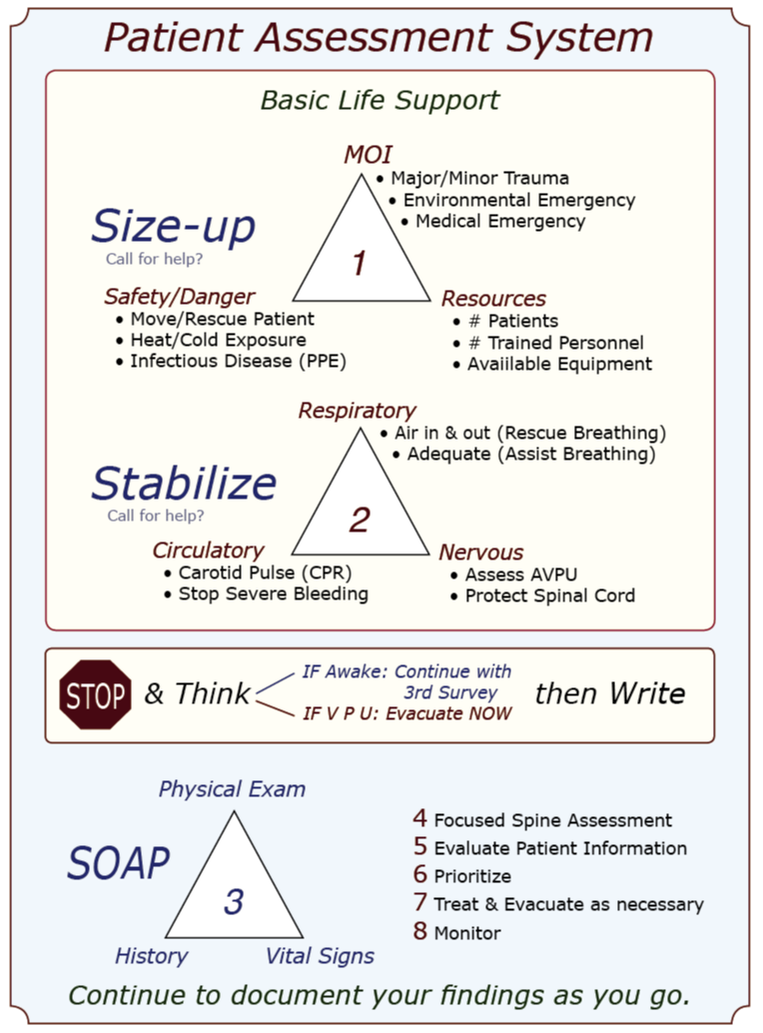

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Mnemonics in CPR and First Aid: A brief history & discussion A mnemonic is a learning technique that enhances information retention or retrieval by associating a concept or action with letters, words, or images. CPR and first aid commonly use letter mnemonics to describe the treatment order during your initial patient assessment; WMTC uses an image or visual mnemonic and builds it into a larger graphic that illustrates our complete patient assessment system. In 1957, Peter Safar, MD, a pioneer in resuscitation techniques, wrote the book ABC of Resuscitation. The ABC mnemonic—airway, breathing, circulation—and its associated techniques were described in a 1962 film, "The Pulse of Life," to promote and bring CPR training to the lay public. The film won six major awards, and the following year, in 1963, the American Heart Association [AHA] officially endorsed CPR; the ABC mnemonic became a standard part of their CPR training program in 1973. The mnemonic was later adopted by the first aid community and used during the initial assessment of an unconscious patient. Because the ABC mnemonic was easy to remember and reflected the order of action as determined by research at the time, it was widely adopted. As interest in outdoor recreational activities—rock climbing, mountaineering, backcountry skiing, white kayaking and rafting, canyoneering, hiking, etc.—grew, enthusiasts and guides alike found that urban first aid courses did not address the needs of remote travelers. With the emergence of wilderness medicine protocols and courses, other letters began to appear in the ABC mnemonic after the C: D for "disability" [referring to the cervical spine], E for "exposure" [to environmental insults], F for "fluids" [blood, cerebrospinal fluid, vomitus, etc.], and even G for "go" [evacuate]. The additional letters had three things in common:

Then, the research data changed the order of the letters in the ABC mnemonic. The AHA found (1) it was slightly more effective — on average roughly 20 seconds faster — to start chest compressions once a rescuer determined a patient was in cardiac arrest than to begin with rescue breathing, especially if a barrier device was used. They found that a person in cardiac arrest from a heart attack had enough residual oxygen in their lungs to oxygenate their brain for 4-6 minutes without rescue breaths if a bystander started pushing on the patient's chest. In 2010, the AHA changed the ABC mnemonic to CAB to reflect the change in treatment and the importance of initiating chest compressions before beginning rescue breathing during CPR when the arrest was due to a heart attack. Note that the ABC mnemonic accurately reflects the treatment order if the cardiac arrest was the result of a primary respiratory problem like drowning, snow burial, lightning, and overdoses where a lack of oxygen caused the arrest. In these cases, it is essential to begin rescue breathing ASAP. During the Middle Eastern wars, the US military found that the rapid application of extremity tourniquets saved lives; in fact, a lot of them. They also discovered that, in some cases, it was possible to apply a tourniquet and later remove it after packing the wound with hemostatic gauze and applying a pressure bandage; this practice saved limbs. Over time, EMS adopted a similar protocol, and instead of tourniquets being used as a last resort to stop severe bleeding, they became the first. To reflect the treatment change, the US military replaced ABC with X-ABC [eXsanguinate, Airway Breathing Circulation] or MARCH [massive hemorrhage, airway, respiration, circulation, head injury/hypothermia]; both of the new mnemonics supported the immediate application of tourniquets to address severe arterial bleeding, rather than the application of direct pressure followed by a pressure bandage with a tourniquet as a last resort. Fortunately, the new data and treatment protocols easily transfer to civilian applications; the mnemonics, however, not so much. Some mnemonics work better than others, depending on the individual, how their mind works, what mnemonic they were taught first, and the situation. Adding additional letters to a classic alphabet mnemonic is pretty easy to do; however, confusion and frustration can set in when a widely accepted alphabet mnemonic changes its letter order under certain situations — like when the AHA changed from ABC to CAB for heart attack patients in cardiac arrest and left ABC in place for arrests due to a primary respiratory problem forcing students to reorient their thinking choose the correct treatment order [and mnemonic].

So, is one mnemonic better than another? As usual, the answer is: It depends. The ABC alphabet mnemonic has been in use since 1957, and almost everyone is familiar with it. With two notable exceptions—cardiac arrest secondary to a heart attack and severe bleeding—it accurately reflects the order of treatment. If you can remember the exceptions, it works. The same is true for the extended alphabet mnemonics. The order of treatment expressed by X-ABC and MARCH works well for tactical situations and is easy for soldiers to remember, but it shares the same exceptions as the ABC alphabet mnemonics. Is WMTC's 3-triangle image mnemonic better? We think so because its ordered but non-linear structure encourages critical thinking and adapts to real-life scenarios and new research better than an entirely linear system. Will it work better for you? Take a course from us, and you decide! Ultimately, the best mnemonic is the one you can remember and use. 1 (2010). 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science. Circulation, 122(18).

Alaska State Epinephrine Law WMTC is an approved Alaska state epinephrine auto-injector training program as per AS 17.22.020. AS 17.22.010 permits individuals who have completed an approved training program to obtain a prescription for an epinephrine auto-injector and use it on another person in an emergency situation. Outfitters to obtain a prescription to purchase epinephrine auto-injectors for staff who have been trained in their use. WMTC graduates may obtain a prescription by presenting their certification card to a physician and referring to the two statutes. In some cases, graduates may need also show the prescribing physician, PA, or nurse practitioner a copy of WMTC's approval letter from the state. Washington State Epinephrine Law WMTC is recognized by Washington State Department of Health as an authorized Epinephrine Auto-injector & Anaphylaxis Training Provider. The law permits healthcare providers to prescribe epinephrine auto-injectors to certified lay providers and REQUIRES the lay provider to report the use of epinephrine within five days of an incident via the departments Epinephrine Auto-injector Incident Reporting Survey online at https://fortress.wa.gov/doh/opinio/s?s=EpinephrineAutoinjector California State Epinephrine Law WMTC is an approved California state epinephrine auto-injector training program. WMTC students issued a WMTC Epinephrine card after April 29, 2019, may apply for a California epinephrine auto-injector certification card and should visit https://emsa.ca.gov/epinephrine_auto_injector/ for information and an application form. Applicants must include a WMTC epinephrine certificate with their application; the certificate is different from the WMTC epinephrine card issued at their course. To obtain a WMTC epinephrine certificate for the State of California application please email [email protected]. Put CA State Epi Certification in the subject line. In the body of the email include:

Upon receipt of the email, our office will verify the student's WMTC epi certification using the above information and send them a pdf file of the certificate for them to print and include in the application for California State Epinephrine Certification; this service is fee of charge to all WMTC graduates. We will also send each student a pdf file summary of our auto-injector curriculum and CA Auto-injector laws. NOTE: California Epinephrine Certificates expire two years from the date a student graduated from their WMTC course. Businesses and other organizations may obtain a prescription and stock epinephrine auto-injectors if they employ or utilize a volunteer that is an EMSA-certified lay rescuer. To receive the epinephrine auto-injector(s), the business must take the EMSA certification card to a physician to receive a prescription. The prescription can then be filled by a pharmacy. A business that stocks epinephrine auto-injectors is required to keep records, create and maintain an operations plan, and report to EMSA when an epinephrine auto-injector is used. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

Erin Genereux, FNP-BC Garrett Genereux, WEMT While death in the backcountry is pretty rare, accidents happen. If the unthinkable occurs and you’re left with the seemingly impossible task of telling the rest of the group or those at home that their friend or loved one has died, the way you deliver the information will affect how it is received. While there is no perfect way to say someone has been severely injured or died, there is language you should avoid. Consider using these talking points:

When notifying or treating expedition members in the field following the delivery of another member's injury or death:

As Kenneth Iserson writes, “No one likes to deliver the news of a sudden, unexpected death to others; it is an emotional blow, precipitating life crises and forever altering their world.” The surviving victim(s) just wants the person telling them the news to show that they care. To show empathy that someone that they loved and cared for has died. If you do your best, you will accomplish what is necessary. Introduction Numerous articles, podcasts, and letters have recently argued for regulating wilderness medicine certifications. At its root, regulation is about control—someone always benefits, and there are always associated costs. This article discusses the various forms of regulation that apply to wilderness medicine certifications and attempts to identify who benefits and at what cost. Once they are known, we can run a cost/benefit analysis and see where it leads us in the near and distant future. Three types of regulation apply to wilderness medicine: economic regulation, government regulation, and self-regulation. Economic Regulation Economics currently regulates the field of wilderness medicine; it's a problematic market-driven, buyer-beware scenario. The Boy Scouts of America, the American Camping Association, and numerous college recreation programs require tripping staff to be certified in Wilderness First Aid. And the outdoor industry recognizes Wilderness First Responder certification as the industry standard for guides and outdoor instructors. Interestingly, course curricula, hours, format, delivery strategies, instructor training, and student assessment and evaluation for both courses vary greatly depending on the provider. Without industry-wide certification standards, potential students, sponsors, employers, and land management agencies have no easy or reliable way to evaluate course curricula or quality. Beneficiaries

Government Regulation Governments enact laws (policies) to control the practice of medicine. In the United States, the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) act of 1973—part of the Public Health Service Act—allocated funds to develop regional EMS systems. States are responsible for training and licensing four levels of first responders: Emergency Medical Responder (EMR), Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), Advanced Emergency Medical Technician (AEMT), and Paramedic. Other countries have similar, but not identical, EMS systems. While numerous schools teach Wilderness EMT (WEMT) or Wilderness EMS (WEMS) courses, wilderness EMS is essentially unregulated on a national or international level. If a country regulated wilderness medicine certifications, it would likely roll the curricula and standards into its existing EMS system. Beneficiaries

Good Samaritan laws protect people who provide first aid at the scene of an accident, act in good faith for the patient's benefit, within their training, and do not receive payment for their services. First aid training addresses the specific needs of a workplace, and the course curriculum tends to vary with the organization; sometimes, this requires advanced training. Graduates of WFA, WAFA, and WFR courses work in remote environments, under challenging conditions, with minimal resources, and in places where traditional EMS is not readily available. Depending on the country and region, some treatment skills taught in wilderness medicine courses may not be considered first aid by local authorities, but practicing medicine and, as such, require a license. Again, depending on the region, a licensed medical advisor with prescribing authority may—or may not—be able to authorize trained staff to administer prescription medications or follow advanced protocols. Self-regulation Two potential self-regulatory options exist—accreditation or industry acceptance of scope of practice documents that set standards for WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications. Accreditation Accreditation is typically the form of self-regulation that initially jumps to mind. If a wilderness medicine school is accredited, an external body has reviewed and approved its curricula, delivery strategies, topics, scope of practice, assessment requirements, instructor hiring, and instructor training guidelines according to a previously agreed-upon set of standards. Accreditation is not a panacea; it does not guarantee quality but indicates an organization has gone through an evaluation process that may improve its operations. Seeking accreditation is voluntary, and the process generally requires a rigorous, often costly, evaluation of the organization's pedagogy with a focus on educational quality. The accrediting body is typically a non-profit organization comprised of widely recognized experts in the field. At present, there is no accrediting body for wilderness medicine schools. Beneficiaries

Certification Standards Voluntary adherence to scope of the Wilderness Education Medicine Collaborative's (WMEC) certification standards documents is another form of self-regulation and a reasonable alternative to accreditation. The documents include a list of topics, skills, and the scope of practice (SOP) required for WFA, WAFA, and WFR graduates. Medically, scope of practice (SOP) documents define the assessment and treatment skills graduates can perform, while curriculum refers to content, delivery, and assessment strategies. Scope of practice, curricula, and certification are related and often overlap. For example, the scope of practice for a ________ graduates may require them be able to recognize and treat _______ As a result, _______ becomes part of the course curriculum; however, the SOP generally will not specify how a school must teach _______. While the WMEC certification standards documents may specify the minimum hours required to teach core material and in-person skill labs and simulations, they typically leave the curriculum details, delivery methods, and assessment strategies to the individual school. The Wilderness Medicine Education Collaborative (WMEC) formed in 2010 to provide a forum for discussing trends and issues in wilderness medicine and to develop consensus-driven scope of practice documents for WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications. In 2022, they expanded their work to include related white papers and position statements. Collectively, the WMEC schools* have over two hundred years of experience teaching wilderness medicine and have trained over 750,000 students in the past four decades. Decisions regarding the content of the WMEC SOPs and papers are made based on emerging research and technology, peer-reviewed articles, and best practices. The WMEC SOP documents provide a basis for certification and curriculum development and are available for public use on the WMEC website. For the WMEC SOP documents to solve the wilderness medicine regulatory problem, international outdoor education and recreation associations must formally recognize them as the industry standard. Examples of industry-wide associations include the Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education (AORE), the Association of Experiential Education (AEE), and the Wilderness Education Association (WEA). Beneficiaries

Conclusion The United States EMS system will likely develop a Wilderness EMS (WEMS) certification in the coming years; however, licensing WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications appear unlikely. That said, there is the possibility that state regulators may push for standardized exams, and if that occurs, the exams will have the potential to impact WFA, WAFA, and WFR course curricula. Creating an accreditation body also seems unlikely due to the expense and resistance from established WFA, WAFA, and WFR schools. Adopting the WMEC certification standards as industry standard for WFA, WAFA, and WFR courses seems the best option now, and into the foreseeable future. Don't know where to begin or what to do? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Introduction A medical advisor who is an active member of your organization's risk management team can help prevent and reduce the severity of program-related injuries and illnesses. We recommend working with a medical advisor who is familiar with your program and an experienced outdoor person. A medical advisor can:

Standing Orders & Protocols Medical advisors use standing orders to authorize treatment and evacuation guidelines to meet an individual program's needs. For the purposes of this document, standing orders are written treatment and evacuation protocols—often in the form of algorithms—that authorize a wilderness medicine provider to complete specific clinical tasks usually reserved by law for licensed physicians (MD, DO, NP), physician assistants (PA), or nurse practitioners (NP) while in the backcountry. Standing orders may be specific to a patient or a condition and take two forms:

Best Practices Standing orders and protocols should:

Examples Examples of standing orders written for an outdoor program or guide service by their medical advisor include:

Interested in learnig more about wilderness medicine? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

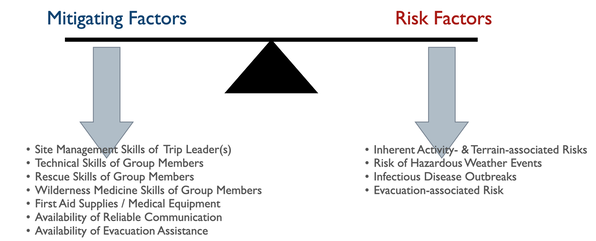

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. All outdoor trips incur risk. Trip planners must balance the severity of a potential injury or illness with the expedition members' outdoor skills, equipment choices, and the availability of outside assistance. The planner must accurately assess each member's skills and other factors with:

Program managers and trip planners often require a deeper understanding of preventative wilderness medicine strategies than most WFR or WEMT graduates possess. A medical advisor who is intimately familiar with the program or trip can recognize clinical conditions for specific medical problems and aid in developing effective mitigation strategies. Let's take a closer look at each risk category: Hazardous Weather Events Due to global warming, hazardous weather events are increasing worldwide, making a trip-related prediction of potential weather-related injuries challenging. In addition to injuries directly associated with weather events, changing microclimates are expanding disease and fauna boundaries, often increasing the range of infectious diseases and venomous creatures. Managers and trip leaders need to:

Inherent Activity- and Terrain-associated Risks Most activity- and terrain-associated hazards are well known within the outdoor industry. Nationally and internationally recognized professional organizations offer training and certification in numerous outdoor pursuits designed to promote best practices within the industry. Both professionals and non-professionals can benefit from these courses and certifications. Training in activity-specific rescue techniques and wilderness medicine, especially Wilderness First Responder, helps expedition members understand potential consequences should things go wrong and imbibe a conservative approach to risk and site management. Infectious Disease Outbreaks Each pathogen, animal vector, and host has an optimal climate in which they thrive, with warm, moist temperate, subtropical, and tropical environments being the best. Global warming has increased and will continue to increase, both temperature and precipitation worldwide, leading to the proliferation of many infectious diseases. While this trend is predictable, the exact type and location of an emerging disease are not, and exposure to and contracting an infectious disease in an area without historical data is increasingly common. To this end, expedition members should protect themselves by treating their water, ensuring good personal and expedition hygiene, taking aggressive precautions against insect-borne diseases, and avoiding potentially infectious animals and their habitat. Avoidance equals prevention, and there are no reliable field treatments for most infectious diseases. Do your research:

Evacuation-associated Injuries The ability—or lack thereof—to rapidly evacuate an injured or ill expedition member to definitive care may directly affect their outcome. Since the inherent risk of injury to rescue party members tends to increase with the severity of the patient's injury or illness, it is critical to diagnose the patient's current and anticipated problems accurately. In some cases, an accurate assessment may require more medical experience than expedition members possess, and a physician consult may be necessary. Any evacuation, regardless of the type or urgency, should not endanger members of the evacuation team or the patient beyond the team's capacity to manage the risk effectively. Interested in Wilderness Medicine? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

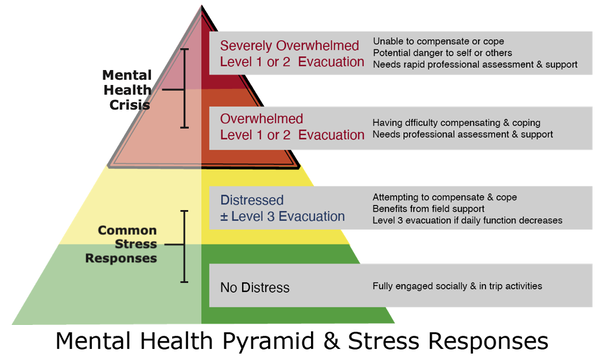

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Stress is inherent in outdoor trips and activities. People can often adapt to mild stress and return to their baseline relatively quickly; however, chronic, moderate, or severe stress may overwhelm an individual’s coping mechanisms and result in a mental health problem. S/Sx include increasing inability to cope with the challenges of the trip, activity, or group. The graphic below depicts the different levels of distress and their associated evacuation levels with respect to a mental health even To help avoid a mental health crisis on expeditions or trips, it is critical to identify and evaluate an individual’s distress early. Check in with the group or individuals daily or after potentially stressful events as part of the expedition culture and stress management. Consider using colors as a tool to help group members self-identify their current stress level.

Green = no distress Yellow = distressed and actively compensating or coping Orange = overwhelmed having difficulty compensating or coping Red = severely overwhelmed and no longer compensating or coping People who self-identify as distressed, overwhelmed, or severely overwhelmed need support and should be encouraged to seek out and speak with staff or the trip leaders privately. Similarly, if staff or trip leaders observe behaviors that indicate a participant may be in distress or crisis, they should speak privately with the individual. Depending on the participant’s story and presenting S/Sx, they may elect to support them in the field or begin an evacuation. S/Sx of Potential Behavioral & Psychological Distress

Support Guidelines Participants who are in distress but actively compensating (yellow) may remain in the field if supported and their daily functioning monitored. Support participants by:

Evacuation Guidelines If any of the following conditions are met, the participant should be evacuated and seen by a mental health professional; closely monitor them during evacuation.

You are a paddle raft guide on the Salmon River during high water; the air temperature is 72º F and water temperature is 54º F. You are at the put-in waiting for your clients to arrive. The bus pulls up and the clients disembark in wetsuits and life-jackets and move to their assigned guides for a safety talk. Your clients all know one another, joined the trip after seeing a brochure during a planned holiday to celebrate the 70th birthdays of two group members, and have never been whitewater rafting before. The entire group is retired, in their late 60s or early 70s, and appear to be in good health for their age. After your safety talk, two of the men, Paul and Andrew, tell you they are each taking a beta blocker for a heart condition. The day run from Riggins to Lucille contains two large rapids where a paddle raft guide needs to rely on the strength and ability of the clients to get the raft to the right place in each rapid; the raft could flip or throw one or more clients in the rapid if in the wrong spot. What are your concerns, if any, and what should you do? Click here to find out. Don't know where to begin or what to do? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed