|

Introduction Numerous articles, podcasts, and letters have recently argued for regulating wilderness medicine certifications. At its root, regulation is about control—someone always benefits, and there are always associated costs. This article discusses the various forms of regulation that apply to wilderness medicine certifications and attempts to identify who benefits and at what cost. Once they are known, we can run a cost/benefit analysis and see where it leads us in the near and distant future. Three types of regulation apply to wilderness medicine: economic regulation, government regulation, and self-regulation. Economic Regulation Economics currently regulates the field of wilderness medicine; it's a problematic market-driven, buyer-beware scenario. The Boy Scouts of America, the American Camping Association, and numerous college recreation programs require tripping staff to be certified in Wilderness First Aid. And the outdoor industry recognizes Wilderness First Responder certification as the industry standard for guides and outdoor instructors. Interestingly, course curricula, hours, format, delivery strategies, instructor training, and student assessment and evaluation for both courses vary greatly depending on the provider. Without industry-wide certification standards, potential students, sponsors, employers, and land management agencies have no easy or reliable way to evaluate course curricula or quality. Beneficiaries

Government Regulation Governments enact laws (policies) to control the practice of medicine. In the United States, the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) act of 1973—part of the Public Health Service Act—allocated funds to develop regional EMS systems. States are responsible for training and licensing four levels of first responders: Emergency Medical Responder (EMR), Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), Advanced Emergency Medical Technician (AEMT), and Paramedic. Other countries have similar, but not identical, EMS systems. While numerous schools teach Wilderness EMT (WEMT) or Wilderness EMS (WEMS) courses, wilderness EMS is essentially unregulated on a national or international level. If a country regulated wilderness medicine certifications, it would likely roll the curricula and standards into its existing EMS system. Beneficiaries

Good Samaritan laws protect people who provide first aid at the scene of an accident, act in good faith for the patient's benefit, within their training, and do not receive payment for their services. First aid training addresses the specific needs of a workplace, and the course curriculum tends to vary with the organization; sometimes, this requires advanced training. Graduates of WFA, WAFA, and WFR courses work in remote environments, under challenging conditions, with minimal resources, and in places where traditional EMS is not readily available. Depending on the country and region, some treatment skills taught in wilderness medicine courses may not be considered first aid by local authorities, but practicing medicine and, as such, require a license. Again, depending on the region, a licensed medical advisor with prescribing authority may—or may not—be able to authorize trained staff to administer prescription medications or follow advanced protocols. Self-regulation Two potential self-regulatory options exist—accreditation or industry acceptance of scope of practice documents that set standards for WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications. Accreditation Accreditation is typically the form of self-regulation that initially jumps to mind. If a wilderness medicine school is accredited, an external body has reviewed and approved its curricula, delivery strategies, topics, scope of practice, assessment requirements, instructor hiring, and instructor training guidelines according to a previously agreed-upon set of standards. Accreditation is not a panacea; it does not guarantee quality but indicates an organization has gone through an evaluation process that may improve its operations. Seeking accreditation is voluntary, and the process generally requires a rigorous, often costly, evaluation of the organization's pedagogy with a focus on educational quality. The accrediting body is typically a non-profit organization comprised of widely recognized experts in the field. At present, there is no accrediting body for wilderness medicine schools. Beneficiaries

Certification Standards Voluntary adherence to scope of the Wilderness Education Medicine Collaborative's (WMEC) certification standards documents is another form of self-regulation and a reasonable alternative to accreditation. The documents include a list of topics, skills, and the scope of practice (SOP) required for WFA, WAFA, and WFR graduates. Medically, scope of practice (SOP) documents define the assessment and treatment skills graduates can perform, while curriculum refers to content, delivery, and assessment strategies. Scope of practice, curricula, and certification are related and often overlap. For example, the scope of practice for a ________ graduates may require them be able to recognize and treat _______ As a result, _______ becomes part of the course curriculum; however, the SOP generally will not specify how a school must teach _______. While the WMEC certification standards documents may specify the minimum hours required to teach core material and in-person skill labs and simulations, they typically leave the curriculum details, delivery methods, and assessment strategies to the individual school. The Wilderness Medicine Education Collaborative (WMEC) formed in 2010 to provide a forum for discussing trends and issues in wilderness medicine and to develop consensus-driven scope of practice documents for WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications. In 2022, they expanded their work to include related white papers and position statements. Collectively, the WMEC schools* have over two hundred years of experience teaching wilderness medicine and have trained over 750,000 students in the past four decades. Decisions regarding the content of the WMEC SOPs and papers are made based on emerging research and technology, peer-reviewed articles, and best practices. The WMEC SOP documents provide a basis for certification and curriculum development and are available for public use on the WMEC website. For the WMEC SOP documents to solve the wilderness medicine regulatory problem, international outdoor education and recreation associations must formally recognize them as the industry standard. Examples of industry-wide associations include the Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education (AORE), the Association of Experiential Education (AEE), and the Wilderness Education Association (WEA). Beneficiaries

Conclusion The United States EMS system will likely develop a Wilderness EMS (WEMS) certification in the coming years; however, licensing WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications appear unlikely. That said, there is the possibility that state regulators may push for standardized exams, and if that occurs, the exams will have the potential to impact WFA, WAFA, and WFR course curricula. Creating an accreditation body also seems unlikely due to the expense and resistance from established WFA, WAFA, and WFR schools. Adopting the WMEC certification standards as industry standard for WFA, WAFA, and WFR courses seems the best option now, and into the foreseeable future. Don't know where to begin or what to do? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

0 Comments

Introduction A medical advisor who is an active member of your organization's risk management team can help prevent and reduce the severity of program-related injuries and illnesses. We recommend working with a medical advisor who is familiar with your program and an experienced outdoor person. A medical advisor can:

Standing Orders & Protocols Medical advisors use standing orders to authorize treatment and evacuation guidelines to meet an individual program's needs. For the purposes of this document, standing orders are written treatment and evacuation protocols—often in the form of algorithms—that authorize a wilderness medicine provider to complete specific clinical tasks usually reserved by law for licensed physicians (MD, DO, NP), physician assistants (PA), or nurse practitioners (NP) while in the backcountry. Standing orders may be specific to a patient or a condition and take two forms:

Best Practices Standing orders and protocols should:

Examples Examples of standing orders written for an outdoor program or guide service by their medical advisor include:

Interested in learnig more about wilderness medicine? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

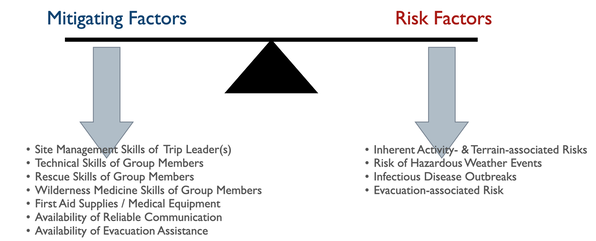

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. All outdoor trips incur risk. Trip planners must balance the severity of a potential injury or illness with the expedition members' outdoor skills, equipment choices, and the availability of outside assistance. The planner must accurately assess each member's skills and other factors with:

Program managers and trip planners often require a deeper understanding of preventative wilderness medicine strategies than most WFR or WEMT graduates possess. A medical advisor who is intimately familiar with the program or trip can recognize clinical conditions for specific medical problems and aid in developing effective mitigation strategies. Let's take a closer look at each risk category: Hazardous Weather Events Due to global warming, hazardous weather events are increasing worldwide, making a trip-related prediction of potential weather-related injuries challenging. In addition to injuries directly associated with weather events, changing microclimates are expanding disease and fauna boundaries, often increasing the range of infectious diseases and venomous creatures. Managers and trip leaders need to:

Inherent Activity- and Terrain-associated Risks Most activity- and terrain-associated hazards are well known within the outdoor industry. Nationally and internationally recognized professional organizations offer training and certification in numerous outdoor pursuits designed to promote best practices within the industry. Both professionals and non-professionals can benefit from these courses and certifications. Training in activity-specific rescue techniques and wilderness medicine, especially Wilderness First Responder, helps expedition members understand potential consequences should things go wrong and imbibe a conservative approach to risk and site management. Infectious Disease Outbreaks Each pathogen, animal vector, and host has an optimal climate in which they thrive, with warm, moist temperate, subtropical, and tropical environments being the best. Global warming has increased and will continue to increase, both temperature and precipitation worldwide, leading to the proliferation of many infectious diseases. While this trend is predictable, the exact type and location of an emerging disease are not, and exposure to and contracting an infectious disease in an area without historical data is increasingly common. To this end, expedition members should protect themselves by treating their water, ensuring good personal and expedition hygiene, taking aggressive precautions against insect-borne diseases, and avoiding potentially infectious animals and their habitat. Avoidance equals prevention, and there are no reliable field treatments for most infectious diseases. Do your research:

Evacuation-associated Injuries The ability—or lack thereof—to rapidly evacuate an injured or ill expedition member to definitive care may directly affect their outcome. Since the inherent risk of injury to rescue party members tends to increase with the severity of the patient's injury or illness, it is critical to diagnose the patient's current and anticipated problems accurately. In some cases, an accurate assessment may require more medical experience than expedition members possess, and a physician consult may be necessary. Any evacuation, regardless of the type or urgency, should not endanger members of the evacuation team or the patient beyond the team's capacity to manage the risk effectively. Interested in Wilderness Medicine? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Introduction Trip medical forms can reduce program liability and help administrators and field staff prevent injuries and illnesses. In most cases, prevention is accomplished through appropriate screening of participants and modifying the structure of a trip by adjusting the trip’s activities and routes to accommodate individual medical conditions or concerns. The type and format of a trip medical form affects the quality of information received and the ability of program administrators and field staff to prevent and treat injuries and illness in the field. Why require medical forms for trips?

How is client medical information collected? Medical information may be collected orally from the client or via a written medical form. Collection is more effective if all involved—client, guide/instructor, healthcare provider, etc.—know why the information is important and how it will be used. There are two basic types of written medical forms: Those completed by a health care professional (physician, PA, or nurse), and those completed by the client (self-reporting). Medical forms completed by a health care professional—especially if they are the client's personal physician—tend to be the most accurate. Those completed by professionals with little or no previous knowledge of the client—college or university clinics, for example—can miss some conditions if the providers rely heavily on patient self-reporting. Self-reporting may be oral or written. Oral self-reporting typically takes place the day of the trip, often as clients are ready to embark on the trip. The accuracy of oral self-reporting is questionable as it's easy for clients to forget something important or simply not mention it for fear they will not be permitted to go on the trip. Clearly written self-reporting forms are better than oral self-reports. Written forms—regardless of whether completed by a healthcare professional or by the client—tend to be more effective when a combination of check boxes and open-ended questions are used. For example, here's a question with Yes/No checkbox followed by a series of open-ended questions asking for more information: "Are you taking any prescription medications?" (Yes/No) "If you answered "yes" to the above question please:

If client medical information is so important, why don't all outdoor programs collect it?

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

This is an excellent practical question! Since students remember the skills and information they use on a regular basis, skill retention is shared by the wilderness medicine provider, their employer(s), and the graduate.

1. Wilderness medicine providers are responsible for:

2. Employers of wilderness medicine graduates are responsible for:

3. Graduates are responsible for:

Follow-up questions include (and will be addressed in later blog articles):

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Outdoor kitchens are fraught with potential danger (really). Typically not life-threatening danger but definitely trip ending danger from cuts, burns, and diarrheal illnesses (gastroenteritis). Aside from sunburn, most burns on outdoor trips happen in or near the kitchen with the vast majority of those due to hot water; the rest tend to involve alcohol and camp fires. Deep cuts occur on a hand when someone holds a bagel or cheese in one hand and wields a knife with the other. Poor hygiene leads to diarrhea.

When you think about it, it's pretty silly to have to leave a trip because of a cut, burn, or an intestinal illness that requires advanced care, especially with a little forethought and planning these type of injuries can be easily avoided. What follows is a summary of good management techniques for outdoor and camp kitchens that focuses on avoidance. Okay, winter IS cold. That's why we call it winter. Cold injuries—hypothermia, frostnip, frostbite, chilblains—are all potential problems. Fortunately with a bit of thought and practice, it's possible to stay warm, even in extreme cold. If you are a seasoned winter traveler, you're probably familiar with everything listed here. If you are new to playing outside in the winter, I trust you'll find a few things of value.

Introduction

Spending time outside for work or play is part of human history, both past and present. Interest in the outdoors is constantly growing with new human-powered and motorized activities/sports emerging on a regular basis. The development of more sophisticated equipment allows access to more challenging terrain and environments...and greater risk. Use permits, once unheard of, are now the rule—and are increasingly difficult to procure for both individuals and organizations. Wilderness ethics are changing as use increases and "leave no trace" has become a mantra for many. In short, the outdoors has become a thriving industry. Designing College & University Outdoor Leadership Recreation, Academic, & Co-curricular Programs12/17/2016 Introduction

Since 1962 when Outward Bound first introduced wilderness adventure programing to United States and the world in the mountains of Colorado, the field has grown exponentially. It is now commonplace to find successful wilderness recreation programs in K-12 schools, summer camps, military bases, and city and state parks. The use of outdoor adventure programs for therapeutic reasons has become it's own industry. And, enrollment in undergraduate and graduate degrees programs in outdoor recreation, education, and therapy is on the upswing. Within the college/university systems there are three types of outdoor programs:

Training outdoor leaders within a college/university setting requires a multidisciplinary approach that does not fit well into a standard quarter/semester format due to the type of terrain and time required teach outdoor skills. The purpose of this article is to briefly discuss the design of each program type, list their pros and cons, and provide a conceptual template for those training students to staff some of their programs. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed