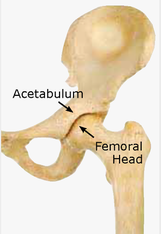

Pathophysiology While posterior hip dislocations are somewhat common in head-on motor vehicle accidents and occasionally occur in elderly people with prosthetic hip joints during a minor slip or fall, they are quite rare in a wilderness environment. Most posterior hip dislocations require a significant traumatic MOI and many patients die from internal injuries to the pelvis, abdomen, chest, and head. Greater than 50% of patients have long-term disability after reduction. The femoral head is highly vascular and may die if not quickly reduced. Posterior hip dislocations are increasing along with the popularity of extreme sports; one study indicated that snowboarders were more likely to suffer a posterior hip dislocation than skiers. The hip joint is a ball-and-socket synovial joint: the ball is the femoral head, and the socket is the acetabulum. The adult hip is quite stable. As such, knee and lower leg injuries are often seen in conjunction with posterior hip dislocations. Due to the potential for significant complications, an attempt should be made to reduce posterior hip dislocations in the field.  Posterior Hip Dislocation Signs & Symptoms

Interested in anticipating and prevention potential problems in the outdoors? What to be able to take care of your family or friends should something unexpected happen? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

0 Comments

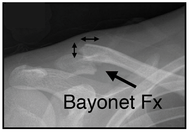

Clavicle Fractures The mechanism of injury is a fall onto an outstretched arm or shoulder, or a direct blow to the clavicle; it is a common mountain bike and snow board injury. Clavicle and first rib fractures typically cause lung damage and respiratory distress. Clavicle Fracture S/Sx

Clavicle Fracture Treatment

Interested in anticipating and prevention potential problems in the outdoors? What to be able to take care of your family or friends should something unexpected happen? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Rib Fractures In most cases, a simple, isolated rib fracture elicits sharp, knife-like pain, and respiratory distress; however, as the patient relaxes and begins to breathe with their diaphragm, the respiratory distress subsides. Depending on the location of the fracture and it's severity, if there are multiple rib fractures especially to the same rib or ribs (flail chest), the patient may present with or develop respiratory distress due to lung damage and/or internal bleeding. Isolated Rib Fracture S/Sx

Interested in anticipating and prevention potential problems in the outdoors? What to be able to take care of your family or friends should something unexpected happen? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

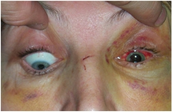

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Similar to patients with skull fractures, patients with an orbital, zygomatic (cheek), nasal, maxillary (mid face), or mandibular (jaw) fracture should be evaluated for a concussion, increased ICP, and a cervical spine injury. Patients with nasal, maxillary, and mandibular fractures may present with or develop airway management problems. Orbital Fractures Orbital Fracture S/Sx

Zygomatic (cheek) Fractures Zygomatic Fracture S/Sx

Nasal Fractures Nasal Fracture S/Sx

Maxillary (mid face) Fracture Maxillary Fracture S/Sx

Mandibular (jaw) Fracture Mandibular Fracture S/Sx

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

The mechanism of injury is clearly head trauma. All patients with a skull fracture should be evaluated for a concussion, increased ICP, and a cervical spine injury, and treated accordingly. Not all patients with a skull fracture present with a loss of consciousness and not all skull fractures require surgery. Exercise caution during the physical exam to avoid compressing a fractured area and further damaging brain tissue. A fracture in conjunction with an overlying wound, or one that communicates with the paranasal sinuses or middle ear often leads to meningitis. Skull Fracture S/Sx

Skull Fracture Treatment

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

Drowning & Traumatic Injuries While the majority of SUP drowning victims were novices not wearing a life-jacket, at least one drowning victim has died on a river when her leash snagged on hidden debris. Death from head injuries is also a concern when examining surf related accidents. And finally, mild traumatic knee and elbow injuries have occurred in whitewater paddlers. Interestingly, much of the protection available is controversial: The pros and cons of wearing, a leash, helmet, or knee & elbow pads are discussed below. To Wear or Not to Wear...a Leash Purchasing and wearing a leash with your paddle board should NOT be a forgone conclusion but it should be a serious consideration. Your board floats. If you don't wear a life-jacket, you will want to keep your board handy. A leash in flat, calm, protected water, especially for novices, may not be necessary and may well impede learning. On the other hand, wearing a leash while touring, in waves, or surf is usually a pretty good idea and will save you a long swim, or worse, should you fall off your board in heavy surf, strong current, or high wind. Wearing a leash in whitewater is a bit controversial. If you spend a lot of time surfing or running high volume rivers, consider a leash. If you run creeks and small rivers with debris and/or mid-river rocks, you probably shouldn't wear one as it increases your chances of entrapment. If you do choose to wear a leash in whitewater, you'll want one that clips to your life-jacket or waist (not your ankle or knee as these are difficult to reach in strong current), has quick release and break-away functions, and practice using it in strong current. If you choose to wear a leash in flat-water or surf and don't typically wear a life-jacket, you'll likely want one that attaches to your ankle or knee. To Wear or Not to Wear...a Life-jacket While wearing a life-jacket definitely increases your safety, they are somewhat constraining, are hot in the summer, interfere with tan-lines, and are therefore, controversial. Your choice to wear one (or not) depends on your paddling background and your risk assessment: Surfers tend to shun life-jackets and rely on their swimming ability and their board's floatation for protection; whitewater paddlers tend to bring and put on a life-jacket out of force of habit; and novices tend to wear what their instructor or friends wear. Manufacturers try to address comfort via design; inflatable life-jackets stored in belt-packs and activated by a pull-tab are available. No life-jacket will maintain an unresponsive person face up in rough water. NOTE: Many states consider paddle boards a water craft and require operators to either wear a life-jacket or have one on board; some states require board to have lights if used after dark. To Wear or Not to Wear...a Helmet Over the years, people have started to wear helmets in lots of sports where they didn't used to: biking, skate boarding, and skiing to name a few...so why not with an SUP? There have been head injuries and deaths in the surfing community (primarily from hitting their board) yet most surfers shun helmets in the same way they do life-jackets. This trend carries over to SUPs. Conversely whitewater paddlers have grown accustomed to wearing a helmet; after all, if you paddle a kayak or C-1, you are essentially tied into your boat with thigh braces and a spray skirt, and being upside down with rocks coming at your head seems to suggest, even to the most brain dead, that a helmet is a good idea. Again, this trend carries over to SUPs. Flat water canoeists and kayakers typically don't wear helmets (not much momentum if you aren't be pushed around by the water) and, once again, this trend carries over to SUPs. Should you wear a helmet? The answer is easy if you've had a previous head injury and are paddling in surf or whitewater: Wear one. Period. For everyone else, it's controversial. You need to make a personal risk assessment and then a decision. Base both on the likelihood of falling and hitting your head (on the board or something else). The bottom line is that it's safer to paddle with a helmet in the surf and whitewater, than not. To Wear or Not to Wear...Body Armor What? Wear body armor? Are you serious? Well, yes, on whitewater (or if you kneel on your board a lot). If you paddle on shallow rivers or tight rivers with lots of exposed rocks you should consider wearing knee and/or elbow pads. Also consider armored shorts with hip and sacral protection. Having your board stop suddenly after scraping the bottom on a rock tends to toss you forward onto the board or into rocks on the bottom of the river. Most paddlers land hard reasonably hard on their knees, elbows, hips, or back. All are somewhat fragile and hurt considerably when abruptly contacting a rock. Pads protect them. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

Introduction Stand up paddle boarding has taken off everywhere there's water: on flat-water, in the surf, and on whitewater. With it come a number of potential problems. Correctly touted as an excellent core workout, a discussion of effective training methods and possible injuries are often overlooked...until something starts to hurt. By then it's too late. Overuse injuries are common. While the overuse injuries in SUP are similar to other paddle sports, they are are exacerbated by the increased leverage of the paddle and the standing position. In order to propel the board forward force must be transmitted from the paddle through the paddler's entire body. Joints are the week points: wrists, elbows, shoulders, back, knees, and ankles. The exact process that makes stand up paddling so good for your core also makes it potentially bad for your joints. There are six things you need to consider when training/paddling SUPs:

Your Paddle You can reduce the strain on your joints by decreasing the length of your paddle, choosing a more flexible paddle shaft, and choosing a small blade size. Decreasing the paddle length directly reduces the size of the lever and therefore the strain on your body. In addition, a shorter paddle lowers your top hand and directly reduces forces on your rotator cuff, shoulder tendons, and cervical spine compression. That said, you don't want a paddle that is too short either as this will cause you to bend over more and increase the strain on your lower back. A flexible paddle shaft absorbs some of the explosive energy during the catch phase of a stroke and spreads the energy release throughout the stroke's length; this dramatically decreases the initial impact on your joints and the potential for damage. Alternatives to carbon-fiber (the stiffest) and fiber-glass blades (next in line) are wood and bamboo. A smaller blade size reduces the surface area of the blade and the amount of energy required for each stroke. While you can purchase smaller blades commercially, you can also cut down the size of your current blade with a jig saw (remember to smooth/sand the edges if you work on your own paddle). Your Body Each individual is unique. Injuries, age, fitness, strength, and flexibility all play an important part in determining what kind of paddling you choose to do and how you approach doing it. For instance, if you have low back problems, it's a better choice to paddle on flat water than in strong whitewater or surf as the sudden movements required for either whitewater paddling or surfing will increase the likelihood of low back injury as you attempt to react to the required changes. Don't ignore your body's history or what it tells you as you paddle and after. Technique Learning the proper paddling technique and paddling on both sides of your board is vital to preventing overuse injuries. Your muscles are designed to be in balance and, in order to prevent injury, you need to keep it that way by learning to paddle correctly on both sides of your board. This may be more difficult that it sounds when surfing or paddling in whitewater as paddlers tend to favor one side or the other. Strength & Flexibility Training If you want to paddle on a regular basis, you'll benefit by spending some time cross-training to avoid injuries. A quick web-search will reveal a number of SUP specific training regimes; one is sure to meet your needs. The Type of Paddling You Do Paddling SUPs on flat-water, in the surf, and on whitewater requires different equipment and skills. The forces on your body are different as well. This means that the types of injuries you can sustain are somewhat specific to the type of paddling you do. Flat-water paddling is typically limited to overuse injuries. While surf and whitewater paddlers are also susceptible to the same overuse injuries as flat-water paddling, moving water is strong and paddling in it increases the chances of muscle and tendon damage; furthermore, traumatic injuries and drowning are also possible. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

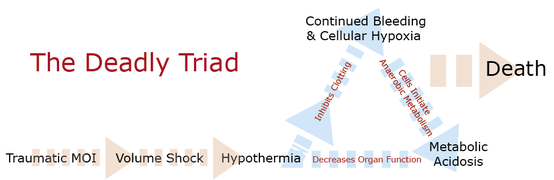

Major traumatic mechanisms often cause life-threatening injuries. If not controlled, those that cause significant internal or external bleeding lead to volume shock and potentially death. It's VITAL that you do everything in your power to keep your patient warm. Here's why: The body responds to blood loss by constricting peripheral blood vessels and increasing their pulse and respiratory rates in an effort to maintain adequate perfusion pressure and a constant supply of nutrients and oxygen to critical organs. As a patient's blood volume drops, their ability to maintain their core temperature also drops and they become increasingly disposed to hypothermia, even in neutral or warm environments. As hypothermia sets in, it interferes with the clotting cascade causing the bleeding to continue further reducing the amount of oxygen reaching the cells. As cells become oxygen-starved, they resort to anaerobic metabolism that ultimately lowers blood pH causing metabolic acidosis that, in turn, damages tissue and organs throughout the patient's body. As organs become damaged, their ability to function also drops, further predisposing the patient to hypothermia. It's a vicious cycle that often ends in death. As such, the importance of keeping trauma patients, especially volume depleted patients, warm cannot be understated. It's important to recognize that injured patients need more insulation—and potentially external heat—than those who are healthy and uninjured; most require a full hypothermia package. That said, be careful not to go overboard and overheat your patient. The skin on their extremities, both hands and feet, should feel warm to the touch when inside the hypothermia package (ensure that your hands are warm); and, if awake, they should not complain of being cold. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

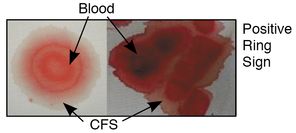

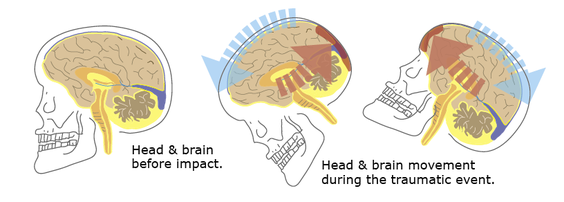

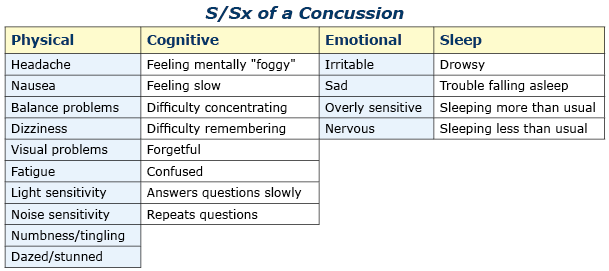

PathophysiologyThe mechanism of injury (MOI) is a direct blow to the patient’s head or a direct blow to another part of their body where the force is transmitted to their brain via their spinal column, cord, and associated soft tissue (aka: whiplash). The brain essentially floats inside the skull in cerebral spinal fluid (CFS). The fluid acts to protect and cushion sensitive brain tissue from minor impacts in much the same way as egg white protects the yolk. If the force generated by the traumatic event is strong enough, the brain will bounce off inside of the skull damaging sensitive brain tissue (as shown in the illustrations below). A concussive injury, should it occur, can be functional or structural. A person with a functional concussive injury will present or develop S/Sx, typically within two hours; however, standard imaging techniques (CT, MRI) show no structural damage. The S/Sx of a functional injury—see the chart below—are likely caused by axional stretching and disruption of ion channels, follow a predefined progression, and usually resolve on their own within 7-10 days; although, in some cases, S/Sx may persist for months. That said, structural damage is possible and may lead to increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and potentially death in rare cases. The concern from a field perspective is whether a person with an apparent positive MOI can remain in the field or requires an evacuation. And, if an evacuation is necessary: What is its urgency? Emergency department physicians typically rely on one of seven clinical algorithms to decide if a patient requires imaging or not (Click here to read an article that discusses the pros and cons of each rule), only the High Risk Criteria for the Canadian CT Head Injury Rule and the NEXUS II can be easily extrapolated to aid evacuation decisions in the field; both may be used in the presence of a significant mechanism of injury. It's important to remember that the guidelines are conservative and few concussed patients go on to develop increased ICP. Assessment All people with a positive mechanism must be evaluated for a potential traumatic brain injury (TBI). TBIs can be grossly subdivided into concussion and increased ICP. Concussions can be further subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe, while increased ICP can be broken down into early and late. After a traumatic MOI a patient may present with any of the problems discussed below and progress, or not, from that point. Note that the problems are mutually exclusive and a patient may only have one problem—concussion or increased ICP—at any given time. Seizures are possible at any point especially in infants and young children and common in unresponsive patients with late increased ICP prior to posturing. Patient's with serious head injuries typically have obvious soft tissue damage to their head including:

Mild Concussion

Moderate Concussion

Severe Concussion The distinction between a moderate and severe concussion is important as the mechanism MAY have been severe enough to structurally injure brain cells or small blood vessels, cause intracranial leaks and swelling, and lead to increased ICP. Worsening S/Sx over the next 24 hours indicate a more severe injury (severe concussion) and can be difficult to recognize if the patient is not closely monitored. Pay close attention to the patient’s overall function: Are their S/Sx severe enough that they interfere with their daily function (severe concussion)? When doubt, choose the worst reasonable case scenario.

Early Increased ICP

Late Increased ICP

Treatment Mild Concussion

Moderate Concussion

Severe Concussion

Early Increased ICP

Late Increased ICP

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and cardiocerebrial resuscitation (CCR) are valuable first aid skills and we should all master them. That said, their effectiveness is severely limited in a wilderness environment. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation uses a combination of chest compressions and rescue breathing to delay brain death and extend the resuscitation window while cardiocerebral resuscitation utilizes chest compressions only; both are potentially life-saving techniques. It takes approximately 10-12 chest compressions to build enough intrathoracic pressure to start circulating blood. The same intrathoracic pressure that circulates the patient’s blood also brings in a small amount of fresh air and oxygen. If there is residual air and oxygen in the lungs—as occurs in cardiac arrest caused by a heart attack—chest compressions alone are more effective in delaying the onset of brain death than when combined with rescue breathing because they maintain a consistent intrathoracic pressure. Conversely, a combination of chest compressions and rescue breathing (CPR) is more effective than CCR for patients whose arrest stems from a primary respiratory problem and lack of available oxygen as occurs in near drowning, lightning, complete snow burial, etc. The effect of both techniques decreases rapidly over time and cannot save or prolong the life of a pulseless patient for greater than 20 minutes and neither CPR or CCR work with major trauma patients whose arrest stems from increased ICP, significant lung damage, or volume shock. For CPR or CCR to be effective the patient’s circulatory system must be intact and their core temperature above 90º F (32º C); your chest compressions must be hard and fast (ideally at least 100 per minute) and delivered in the lower third of the patient’s sternum; your weight must be directly over the patient and the patient’s chest must be allowed to fully recoil between compressions; the recoil is as important as the compression. If rescue breathing is indicated, ventilate until the patient’s chest begins to rise; do not over-inflate—over-inflation forces air into the patient’s stomach and increases the chance or frequency of vomiting. In settings where rapid defibrillation, advanced cardiac life support, and rapid transport to a major hospital are not possible, the overwhelming majority of patients in cardiac arrest will die. It is important that all rescuers understand the limits of CPR and CCR and when it is appropriate to start and stop. When teaching chest compressions in our wilderness medicine courses we often tell students to compress at the rate of the beat in the Bee Gee's disco tune "Staying Alive" or Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust" depending on whether a student views the glass as half full or half empty.... (Yes, humor is important in the medical field.) Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed