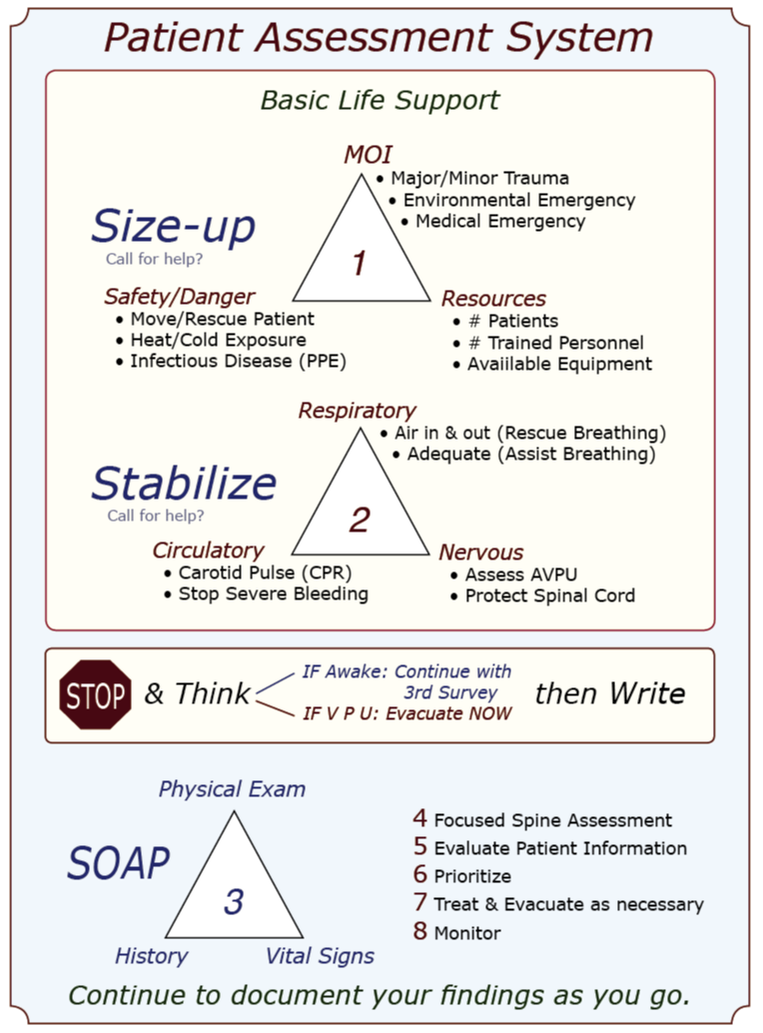

Mnemonics in CPR and First Aid: A brief history & discussion A mnemonic is a learning technique that enhances information retention or retrieval by associating a concept or action with letters, words, or images. CPR and first aid commonly use letter mnemonics to describe the treatment order during your initial patient assessment; WMTC uses an image or visual mnemonic and builds it into a larger graphic that illustrates our complete patient assessment system. In 1957, Peter Safar, MD, a pioneer in resuscitation techniques, wrote the book ABC of Resuscitation. The ABC mnemonic—airway, breathing, circulation—and its associated techniques were described in a 1962 film, "The Pulse of Life," to promote and bring CPR training to the lay public. The film won six major awards, and the following year, in 1963, the American Heart Association [AHA] officially endorsed CPR; the ABC mnemonic became a standard part of their CPR training program in 1973. The mnemonic was later adopted by the first aid community and used during the initial assessment of an unconscious patient. Because the ABC mnemonic was easy to remember and reflected the order of action as determined by research at the time, it was widely adopted. As interest in outdoor recreational activities—rock climbing, mountaineering, backcountry skiing, white kayaking and rafting, canyoneering, hiking, etc.—grew, enthusiasts and guides alike found that urban first aid courses did not address the needs of remote travelers. With the emergence of wilderness medicine protocols and courses, other letters began to appear in the ABC mnemonic after the C: D for "disability" [referring to the cervical spine], E for "exposure" [to environmental insults], F for "fluids" [blood, cerebrospinal fluid, vomitus, etc.], and even G for "go" [evacuate]. The additional letters had three things in common:

Then, the research data changed the order of the letters in the ABC mnemonic. The AHA found (1) it was slightly more effective — on average roughly 20 seconds faster — to start chest compressions once a rescuer determined a patient was in cardiac arrest than to begin with rescue breathing, especially if a barrier device was used. They found that a person in cardiac arrest from a heart attack had enough residual oxygen in their lungs to oxygenate their brain for 4-6 minutes without rescue breaths if a bystander started pushing on the patient's chest. In 2010, the AHA changed the ABC mnemonic to CAB to reflect the change in treatment and the importance of initiating chest compressions before beginning rescue breathing during CPR when the arrest was due to a heart attack. Note that the ABC mnemonic accurately reflects the treatment order if the cardiac arrest was the result of a primary respiratory problem like drowning, snow burial, lightning, and overdoses where a lack of oxygen caused the arrest. In these cases, it is essential to begin rescue breathing ASAP. During the Middle Eastern wars, the US military found that the rapid application of extremity tourniquets saved lives; in fact, a lot of them. They also discovered that, in some cases, it was possible to apply a tourniquet and later remove it after packing the wound with hemostatic gauze and applying a pressure bandage; this practice saved limbs. Over time, EMS adopted a similar protocol, and instead of tourniquets being used as a last resort to stop severe bleeding, they became the first. To reflect the treatment change, the US military replaced ABC with X-ABC [eXsanguinate, Airway Breathing Circulation] or MARCH [massive hemorrhage, airway, respiration, circulation, head injury/hypothermia]; both of the new mnemonics supported the immediate application of tourniquets to address severe arterial bleeding, rather than the application of direct pressure followed by a pressure bandage with a tourniquet as a last resort. Fortunately, the new data and treatment protocols easily transfer to civilian applications; the mnemonics, however, not so much. Some mnemonics work better than others, depending on the individual, how their mind works, what mnemonic they were taught first, and the situation. Adding additional letters to a classic alphabet mnemonic is pretty easy to do; however, confusion and frustration can set in when a widely accepted alphabet mnemonic changes its letter order under certain situations — like when the AHA changed from ABC to CAB for heart attack patients in cardiac arrest and left ABC in place for arrests due to a primary respiratory problem forcing students to reorient their thinking choose the correct treatment order [and mnemonic].

So, is one mnemonic better than another? As usual, the answer is: It depends. The ABC alphabet mnemonic has been in use since 1957, and almost everyone is familiar with it. With two notable exceptions—cardiac arrest secondary to a heart attack and severe bleeding—it accurately reflects the order of treatment. If you can remember the exceptions, it works. The same is true for the extended alphabet mnemonics. The order of treatment expressed by X-ABC and MARCH works well for tactical situations and is easy for soldiers to remember, but it shares the same exceptions as the ABC alphabet mnemonics. Is WMTC's 3-triangle image mnemonic better? We think so because its ordered but non-linear structure encourages critical thinking and adapts to real-life scenarios and new research better than an entirely linear system. Will it work better for you? Take a course from us, and you decide! Ultimately, the best mnemonic is the one you can remember and use. 1 (2010). 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science. Circulation, 122(18).

0 Comments

Erin Genereux, FNP-BC Garrett Genereux, WEMT While death in the backcountry is pretty rare, accidents happen. If the unthinkable occurs and you’re left with the seemingly impossible task of telling the rest of the group or those at home that their friend or loved one has died, the way you deliver the information will affect how it is received. While there is no perfect way to say someone has been severely injured or died, there is language you should avoid. Consider using these talking points:

When notifying or treating expedition members in the field following the delivery of another member's injury or death:

As Kenneth Iserson writes, “No one likes to deliver the news of a sudden, unexpected death to others; it is an emotional blow, precipitating life crises and forever altering their world.” The surviving victim(s) just wants the person telling them the news to show that they care. To show empathy that someone that they loved and cared for has died. If you do your best, you will accomplish what is necessary. Introduction Numerous articles, podcasts, and letters have recently argued for regulating wilderness medicine certifications. At its root, regulation is about control—someone always benefits, and there are always associated costs. This article discusses the various forms of regulation that apply to wilderness medicine certifications and attempts to identify who benefits and at what cost. Once they are known, we can run a cost/benefit analysis and see where it leads us in the near and distant future. Three types of regulation apply to wilderness medicine: economic regulation, government regulation, and self-regulation. Economic Regulation Economics currently regulates the field of wilderness medicine; it's a problematic market-driven, buyer-beware scenario. The Boy Scouts of America, the American Camping Association, and numerous college recreation programs require tripping staff to be certified in Wilderness First Aid. And the outdoor industry recognizes Wilderness First Responder certification as the industry standard for guides and outdoor instructors. Interestingly, course curricula, hours, format, delivery strategies, instructor training, and student assessment and evaluation for both courses vary greatly depending on the provider. Without industry-wide certification standards, potential students, sponsors, employers, and land management agencies have no easy or reliable way to evaluate course curricula or quality. Beneficiaries

Government Regulation Governments enact laws (policies) to control the practice of medicine. In the United States, the Emergency Medical Services (EMS) act of 1973—part of the Public Health Service Act—allocated funds to develop regional EMS systems. States are responsible for training and licensing four levels of first responders: Emergency Medical Responder (EMR), Emergency Medical Technician (EMT), Advanced Emergency Medical Technician (AEMT), and Paramedic. Other countries have similar, but not identical, EMS systems. While numerous schools teach Wilderness EMT (WEMT) or Wilderness EMS (WEMS) courses, wilderness EMS is essentially unregulated on a national or international level. If a country regulated wilderness medicine certifications, it would likely roll the curricula and standards into its existing EMS system. Beneficiaries

Good Samaritan laws protect people who provide first aid at the scene of an accident, act in good faith for the patient's benefit, within their training, and do not receive payment for their services. First aid training addresses the specific needs of a workplace, and the course curriculum tends to vary with the organization; sometimes, this requires advanced training. Graduates of WFA, WAFA, and WFR courses work in remote environments, under challenging conditions, with minimal resources, and in places where traditional EMS is not readily available. Depending on the country and region, some treatment skills taught in wilderness medicine courses may not be considered first aid by local authorities, but practicing medicine and, as such, require a license. Again, depending on the region, a licensed medical advisor with prescribing authority may—or may not—be able to authorize trained staff to administer prescription medications or follow advanced protocols. Self-regulation Two potential self-regulatory options exist—accreditation or industry acceptance of scope of practice documents that set standards for WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications. Accreditation Accreditation is typically the form of self-regulation that initially jumps to mind. If a wilderness medicine school is accredited, an external body has reviewed and approved its curricula, delivery strategies, topics, scope of practice, assessment requirements, instructor hiring, and instructor training guidelines according to a previously agreed-upon set of standards. Accreditation is not a panacea; it does not guarantee quality but indicates an organization has gone through an evaluation process that may improve its operations. Seeking accreditation is voluntary, and the process generally requires a rigorous, often costly, evaluation of the organization's pedagogy with a focus on educational quality. The accrediting body is typically a non-profit organization comprised of widely recognized experts in the field. At present, there is no accrediting body for wilderness medicine schools. Beneficiaries

Certification Standards Voluntary adherence to scope of the Wilderness Education Medicine Collaborative's (WMEC) certification standards documents is another form of self-regulation and a reasonable alternative to accreditation. The documents include a list of topics, skills, and the scope of practice (SOP) required for WFA, WAFA, and WFR graduates. Medically, scope of practice (SOP) documents define the assessment and treatment skills graduates can perform, while curriculum refers to content, delivery, and assessment strategies. Scope of practice, curricula, and certification are related and often overlap. For example, the scope of practice for a ________ graduates may require them be able to recognize and treat _______ As a result, _______ becomes part of the course curriculum; however, the SOP generally will not specify how a school must teach _______. While the WMEC certification standards documents may specify the minimum hours required to teach core material and in-person skill labs and simulations, they typically leave the curriculum details, delivery methods, and assessment strategies to the individual school. The Wilderness Medicine Education Collaborative (WMEC) formed in 2010 to provide a forum for discussing trends and issues in wilderness medicine and to develop consensus-driven scope of practice documents for WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications. In 2022, they expanded their work to include related white papers and position statements. Collectively, the WMEC schools* have over two hundred years of experience teaching wilderness medicine and have trained over 750,000 students in the past four decades. Decisions regarding the content of the WMEC SOPs and papers are made based on emerging research and technology, peer-reviewed articles, and best practices. The WMEC SOP documents provide a basis for certification and curriculum development and are available for public use on the WMEC website. For the WMEC SOP documents to solve the wilderness medicine regulatory problem, international outdoor education and recreation associations must formally recognize them as the industry standard. Examples of industry-wide associations include the Association of Outdoor Recreation and Education (AORE), the Association of Experiential Education (AEE), and the Wilderness Education Association (WEA). Beneficiaries

Conclusion The United States EMS system will likely develop a Wilderness EMS (WEMS) certification in the coming years; however, licensing WFA, WAFA, and WFR certifications appear unlikely. That said, there is the possibility that state regulators may push for standardized exams, and if that occurs, the exams will have the potential to impact WFA, WAFA, and WFR course curricula. Creating an accreditation body also seems unlikely due to the expense and resistance from established WFA, WAFA, and WFR schools. Adopting the WMEC certification standards as industry standard for WFA, WAFA, and WFR courses seems the best option now, and into the foreseeable future. Don't know where to begin or what to do? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Introduction A medical advisor who is an active member of your organization's risk management team can help prevent and reduce the severity of program-related injuries and illnesses. We recommend working with a medical advisor who is familiar with your program and an experienced outdoor person. A medical advisor can:

Standing Orders & Protocols Medical advisors use standing orders to authorize treatment and evacuation guidelines to meet an individual program's needs. For the purposes of this document, standing orders are written treatment and evacuation protocols—often in the form of algorithms—that authorize a wilderness medicine provider to complete specific clinical tasks usually reserved by law for licensed physicians (MD, DO, NP), physician assistants (PA), or nurse practitioners (NP) while in the backcountry. Standing orders may be specific to a patient or a condition and take two forms:

Best Practices Standing orders and protocols should:

Examples Examples of standing orders written for an outdoor program or guide service by their medical advisor include:

Interested in learnig more about wilderness medicine? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

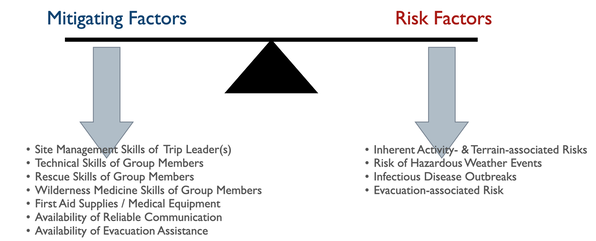

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. All outdoor trips incur risk. Trip planners must balance the severity of a potential injury or illness with the expedition members' outdoor skills, equipment choices, and the availability of outside assistance. The planner must accurately assess each member's skills and other factors with:

Program managers and trip planners often require a deeper understanding of preventative wilderness medicine strategies than most WFR or WEMT graduates possess. A medical advisor who is intimately familiar with the program or trip can recognize clinical conditions for specific medical problems and aid in developing effective mitigation strategies. Let's take a closer look at each risk category: Hazardous Weather Events Due to global warming, hazardous weather events are increasing worldwide, making a trip-related prediction of potential weather-related injuries challenging. In addition to injuries directly associated with weather events, changing microclimates are expanding disease and fauna boundaries, often increasing the range of infectious diseases and venomous creatures. Managers and trip leaders need to:

Inherent Activity- and Terrain-associated Risks Most activity- and terrain-associated hazards are well known within the outdoor industry. Nationally and internationally recognized professional organizations offer training and certification in numerous outdoor pursuits designed to promote best practices within the industry. Both professionals and non-professionals can benefit from these courses and certifications. Training in activity-specific rescue techniques and wilderness medicine, especially Wilderness First Responder, helps expedition members understand potential consequences should things go wrong and imbibe a conservative approach to risk and site management. Infectious Disease Outbreaks Each pathogen, animal vector, and host has an optimal climate in which they thrive, with warm, moist temperate, subtropical, and tropical environments being the best. Global warming has increased and will continue to increase, both temperature and precipitation worldwide, leading to the proliferation of many infectious diseases. While this trend is predictable, the exact type and location of an emerging disease are not, and exposure to and contracting an infectious disease in an area without historical data is increasingly common. To this end, expedition members should protect themselves by treating their water, ensuring good personal and expedition hygiene, taking aggressive precautions against insect-borne diseases, and avoiding potentially infectious animals and their habitat. Avoidance equals prevention, and there are no reliable field treatments for most infectious diseases. Do your research:

Evacuation-associated Injuries The ability—or lack thereof—to rapidly evacuate an injured or ill expedition member to definitive care may directly affect their outcome. Since the inherent risk of injury to rescue party members tends to increase with the severity of the patient's injury or illness, it is critical to diagnose the patient's current and anticipated problems accurately. In some cases, an accurate assessment may require more medical experience than expedition members possess, and a physician consult may be necessary. Any evacuation, regardless of the type or urgency, should not endanger members of the evacuation team or the patient beyond the team's capacity to manage the risk effectively. Interested in Wilderness Medicine? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Introduction Trip medical forms can reduce program liability and help administrators and field staff prevent injuries and illnesses. In most cases, prevention is accomplished through appropriate screening of participants and modifying the structure of a trip by adjusting the trip’s activities and routes to accommodate individual medical conditions or concerns. The type and format of a trip medical form affects the quality of information received and the ability of program administrators and field staff to prevent and treat injuries and illness in the field. Why require medical forms for trips?

How is client medical information collected? Medical information may be collected orally from the client or via a written medical form. Collection is more effective if all involved—client, guide/instructor, healthcare provider, etc.—know why the information is important and how it will be used. There are two basic types of written medical forms: Those completed by a health care professional (physician, PA, or nurse), and those completed by the client (self-reporting). Medical forms completed by a health care professional—especially if they are the client's personal physician—tend to be the most accurate. Those completed by professionals with little or no previous knowledge of the client—college or university clinics, for example—can miss some conditions if the providers rely heavily on patient self-reporting. Self-reporting may be oral or written. Oral self-reporting typically takes place the day of the trip, often as clients are ready to embark on the trip. The accuracy of oral self-reporting is questionable as it's easy for clients to forget something important or simply not mention it for fear they will not be permitted to go on the trip. Clearly written self-reporting forms are better than oral self-reports. Written forms—regardless of whether completed by a healthcare professional or by the client—tend to be more effective when a combination of check boxes and open-ended questions are used. For example, here's a question with Yes/No checkbox followed by a series of open-ended questions asking for more information: "Are you taking any prescription medications?" (Yes/No) "If you answered "yes" to the above question please:

If client medical information is so important, why don't all outdoor programs collect it?

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

(What are they and should I join one?) With the worldwide increase in natural disasters, wilderness medicine graduates are uniquely poised to help their neighbors in the event of a local disaster. Communities in all 50 states have organized Community Emergency Response Teams (CERT). CERT members are volunteers, and teams are structured so that local managers have the flexibility to adapt the program and their training to the specific needs of their community. The concept originated with the Los Angeles City Fire Department in 1985 and went national through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 1993. Contact your local fire, police, or sheriff department for more information or visit the CERT website.

(What to do when someone dies in the backcountry.) Deaths in the backcountry are rare, exactly how rare is up for debate. Much depends on how you define backcountry and where you get your numbers (outside of the National Park Service, accurate statistics are hard to find). That said, a few hundred people appear to die each year while recreating in the outdoors. Given the number of people who play outside annually, statistically, death is pretty rare. While the order often changes annually, the top ten causes of death in the backcountry appear to be:

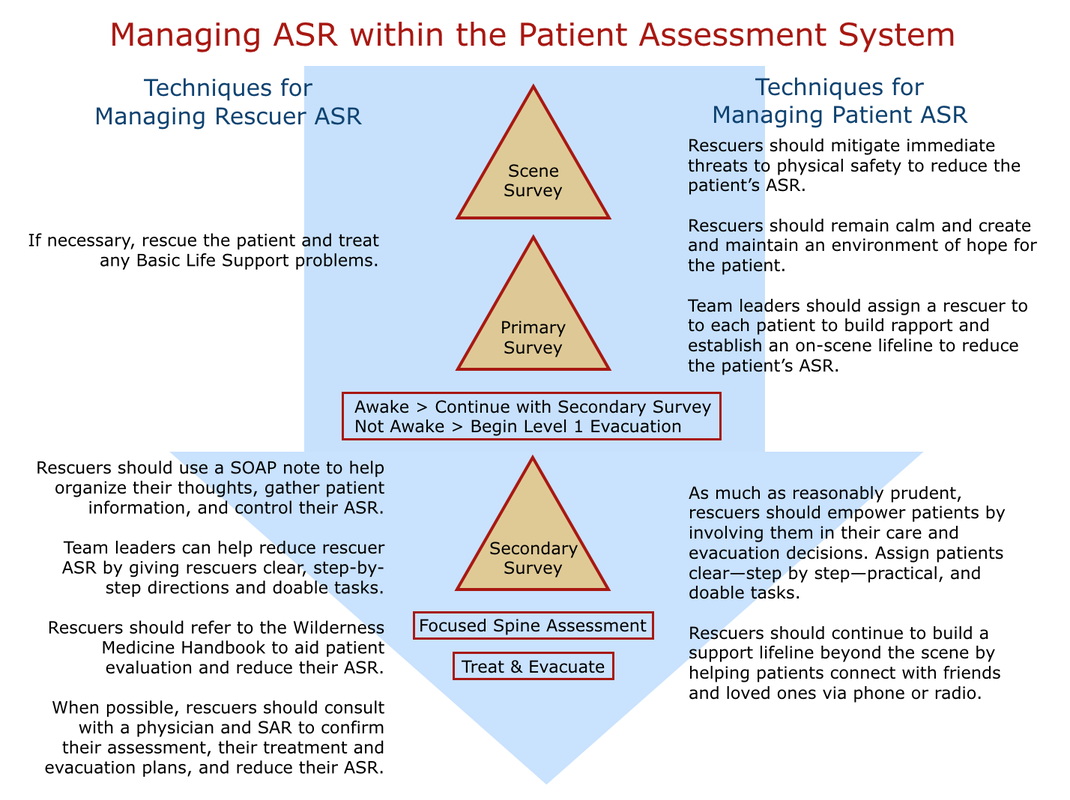

So what should I do if I'm with a person who is dying? There is no single answer that applies to all people other than support their process to the best of your ability. For many, this means holding their hand and simply being present. For some, it may include praying with or for them. If the person is awake, it may mean taking notes to share with relatives and friends. The specifics vary from individual to individual. How do I know when a person is dead? They will not have any signs of life: no pulse at their carotid artery, no chest rise, and no air coming from their mouth or nose. Over time their body will cool until it reaches the ambient air temperature and rigor mortis and liver mortis will set in. Rigor Mortis: When energy is no longer being produced, muscles contract and stiffen beginning with the small muscles of the face, neck, arms, and shoulders and gradually encompassing larger muscles until the person's body is completely stiff. Rigor is typically fully set within eight hours and remains in place for roughly eighteen hours before reversing itself to pre-rigor status, starting with the large muscles. Liver Mortis: When a person's blood stops circulating after death, gravity causes the red blood cells to settle leaving dark "bruising" in areas of the patient's body that are in contact with the ground. The process begins roughly thirty minutes after death and is fixed after approximately six hours. What should I do after a person is dead? Keep in mind that your first priority is yourself and the living members of your party. Make sure everyone is safe. Then, if possible, note the GPS coordinates of the body's location and notify the local authorities via radio, cell phone, satellite phone, or other communication device and follow their instructions. If the dead person was your patient, complete a SOAP note. If they were a client or student, also complete your program's accident/incident report form. Take pictures of the site and body, especially if the mechanism was trauma, and do your best to preserve the scene for the authorities; most states prohibit moving a dead body from the scene of the accident without the authority of the coroner. Of course, some scenes cannot be preserved due to weather or terrain. If you can't contact and receive direction from local authorities and find you must leave the scene, your photos become evidence and part of any subsequent investigation. If you decide to leave the scene and the body, do your best to protect the body from scavengers and clearly mark its location both visually and on a map. Although rare, some expeditions have decided to transport the body of the deceased out of the backcountry. Treat the body with respect and be sensitive to the cultural mores of the deceased and those around you. On a functional level, the nervous system is divided into two divisions: the voluntary (somatic) nervous system and the involuntary (autonomic) nervous system. The voluntary division of the nervous system contains both sensory and motor nerves. Sensory nerves carry input to the spinal cord and brain, while motor nerves carry messages from them. Through its nerves, the somatic nervous system controls conscious functions, principally high-level thought and striated muscle contractions. The autonomic division maintains or restores homeostasis by regulating smooth muscle contractions and the glandular secretion of hormones. Most autonomic functions are beyond conscious control. The autonomic division of the nervous system is subdivided into the sympathetic and the parasympathetic systems. The sympathetic system stimulates effectors (cells or organs) while the parasympathetic system inhibits them. Both systems continually transmit impulses to the same effector and act in an antagonistic manner, with the stronger impulse assuming control. Under normal conditions, the sympathetic system is responsible for waking us up and the parasympathetic system is responsible for sleep and digestion. If the sympathetic nervous system is engaged during a stress response, the body prepares for “fight or flight”: pupils dilate to increase vision; pulse, respiration and blood pressure rates rise to meet an intense physical demand; awareness, often seen as anxiety, increases; sweating increases, while vasoconstriction leaves the skin pale, cool and moist; and endorphins are released to block pain. Over stimulation of muscle fibers often results in uncontrollable shaking. A strong sympathetic response decreases cognitive function leaving patients unable to process complex information and feeling overwhelmed and often fearful. A patient experiencing a sympathetic ASR cannot give accurate information about their injuries. In most cases, they are unaware of any physical injuries and may not exhibit abnormal signs or symptoms upon examination. Their vital sign pattern may mimic or mask volume shock. If the parasympathetic nervous system is stimulated, the patient becomes nauseated, dizzy, and may faint. Blood pools centrally around their digestive tract and their pulse, respiratory and blood pressure rates fall. Their skin is pale and cool. Upon awakening, the patient is often confused. A parasympathetic ASR may mimic the signs and symptoms of a concussion and make accurate assessment of a traumatic head injury difficult. A serious medical incident is often stressful to all involved: rescuers, care providers, patients, and bystanders; and, any or all involved may have both immediate and lingering effects: Post Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) are common, although individual reactions vary considerably. Your actions as a rescuer or care provider can mitigate your patient's stress in both the short term and long term. And as a scene leader, the same strategies apply to working with expedition members or your rescue team and bystanders. The term "Psychological First Aid (PFA)" has been used in recent years to identify strategies that have proven to help prevent or reduce both the short (ASR) and long term (PTSD) effects of stress. While the term may be new, the strategies discussed below should not be: Psychological First Aid is—and has been—an intentional and integral part of our Patient Assessment System. The strategies below align with current PFA principles. As much as possible, rescuers should strive to create as safe an environment as possible in the aftermath of an overwhelming event by mitigating scene threats and calming patients, bystanders, and rescuers as necessary. It's vital not to lie to patients, bystanders, or team members but to be realistic and focus on what you—and they—can do, and are doing to keep them safe. This may include removing select people from the scene or shielding them from a chaotic scene. Remember that stress affects everyone, including rescuers and care providers. You must first reduce your sympathetic ASR (fight or flight response) before attempting to help others. Again, be truthful and focus on the present. As much as possible, radiate calm. Following the Patient Assessment System and using SOAP notes help caregivers reduce their ASR by providing an organized, step by step thought process, that also acts to calm their patients. It's easy for both patients and rescuers to feel powerless or helpless in what they perceive as extreme situations where no clear avenue forward is visible. Care providers can empower patients by involving them in their care and evacuation decisions where appropriate, and where appropriate in the care of others. And team leaders can empower rescuers, care providers, and bystanders by assigning clear—step by step—practical, and doable tasks. Team leaders can also build an on-scene support network by assigning a care provider to each patient and have them remain with the patient throughout their assessment, treatment, and evacuation (they do not have to be the primary care provider). The relationship between a care provider and patient provides a very real lifeline for severely stressed patients. Both team leaders and care providers can also work to extend the support lifeline beyond the scene by helping patients and bystanders connect with their friends, family, and pets as soon as possible. ln combination with shared, relevant stories, all of the above combine to help inspire hope for the current situation. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

In combination with our patient assessment system and field handbook, we use SOAP notes to help teach students how to assess and treat patients. They quickly see the benefit in a well-designed SOAP note, especially for complex problems; however, they often question if a SOAP note should be used for every patient? After all they take time to complete (and everyone hates paperwork, particularly if it's seen as unnecessary). So...what's necessary and what isn't? Sometimes the answer is obvious: The problem is serious and/or complex and a SOAP note is necessary. But what about minor problems, for example: blisters, strains and sprains, cuts, etc.; and problems that may, or may not, develop into something more serious, like hymenoptera stings that may progress to anaphylaxis, a blow to the head that may turn out to be a mild concussion, or a drowning patient who was awake throughout their rescue but coughing, etc. These are not so obvious, usually because they don't require an evacuation at the moment...but could in the future. What about them? There are a couple of ways to proceed; both are valid:

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

Download a free pdf copy of our 2018 SOAP note for you personal or institutional use; print on 8.5 x 14 legal paper and fold into thirds. Many not be used to teach © 2018 WMTC. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed