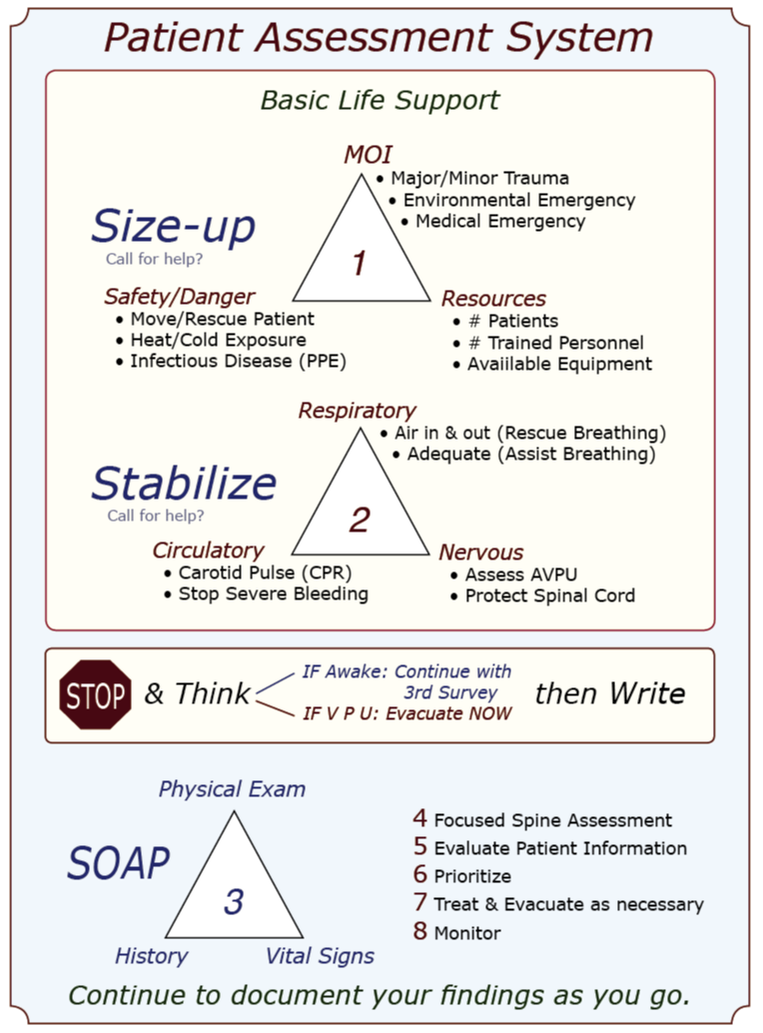

Mnemonics in CPR and First Aid: A brief history & discussion A mnemonic is a learning technique that enhances information retention or retrieval by associating a concept or action with letters, words, or images. CPR and first aid commonly use letter mnemonics to describe the treatment order during your initial patient assessment; WMTC uses an image or visual mnemonic and builds it into a larger graphic that illustrates our complete patient assessment system. In 1957, Peter Safar, MD, a pioneer in resuscitation techniques, wrote the book ABC of Resuscitation. The ABC mnemonic—airway, breathing, circulation—and its associated techniques were described in a 1962 film, "The Pulse of Life," to promote and bring CPR training to the lay public. The film won six major awards, and the following year, in 1963, the American Heart Association [AHA] officially endorsed CPR; the ABC mnemonic became a standard part of their CPR training program in 1973. The mnemonic was later adopted by the first aid community and used during the initial assessment of an unconscious patient. Because the ABC mnemonic was easy to remember and reflected the order of action as determined by research at the time, it was widely adopted. As interest in outdoor recreational activities—rock climbing, mountaineering, backcountry skiing, white kayaking and rafting, canyoneering, hiking, etc.—grew, enthusiasts and guides alike found that urban first aid courses did not address the needs of remote travelers. With the emergence of wilderness medicine protocols and courses, other letters began to appear in the ABC mnemonic after the C: D for "disability" [referring to the cervical spine], E for "exposure" [to environmental insults], F for "fluids" [blood, cerebrospinal fluid, vomitus, etc.], and even G for "go" [evacuate]. The additional letters had three things in common:

Then, the research data changed the order of the letters in the ABC mnemonic. The AHA found (1) it was slightly more effective — on average roughly 20 seconds faster — to start chest compressions once a rescuer determined a patient was in cardiac arrest than to begin with rescue breathing, especially if a barrier device was used. They found that a person in cardiac arrest from a heart attack had enough residual oxygen in their lungs to oxygenate their brain for 4-6 minutes without rescue breaths if a bystander started pushing on the patient's chest. In 2010, the AHA changed the ABC mnemonic to CAB to reflect the change in treatment and the importance of initiating chest compressions before beginning rescue breathing during CPR when the arrest was due to a heart attack. Note that the ABC mnemonic accurately reflects the treatment order if the cardiac arrest was the result of a primary respiratory problem like drowning, snow burial, lightning, and overdoses where a lack of oxygen caused the arrest. In these cases, it is essential to begin rescue breathing ASAP. During the Middle Eastern wars, the US military found that the rapid application of extremity tourniquets saved lives; in fact, a lot of them. They also discovered that, in some cases, it was possible to apply a tourniquet and later remove it after packing the wound with hemostatic gauze and applying a pressure bandage; this practice saved limbs. Over time, EMS adopted a similar protocol, and instead of tourniquets being used as a last resort to stop severe bleeding, they became the first. To reflect the treatment change, the US military replaced ABC with X-ABC [eXsanguinate, Airway Breathing Circulation] or MARCH [massive hemorrhage, airway, respiration, circulation, head injury/hypothermia]; both of the new mnemonics supported the immediate application of tourniquets to address severe arterial bleeding, rather than the application of direct pressure followed by a pressure bandage with a tourniquet as a last resort. Fortunately, the new data and treatment protocols easily transfer to civilian applications; the mnemonics, however, not so much. Some mnemonics work better than others, depending on the individual, how their mind works, what mnemonic they were taught first, and the situation. Adding additional letters to a classic alphabet mnemonic is pretty easy to do; however, confusion and frustration can set in when a widely accepted alphabet mnemonic changes its letter order under certain situations — like when the AHA changed from ABC to CAB for heart attack patients in cardiac arrest and left ABC in place for arrests due to a primary respiratory problem forcing students to reorient their thinking choose the correct treatment order [and mnemonic].

So, is one mnemonic better than another? As usual, the answer is: It depends. The ABC alphabet mnemonic has been in use since 1957, and almost everyone is familiar with it. With two notable exceptions—cardiac arrest secondary to a heart attack and severe bleeding—it accurately reflects the order of treatment. If you can remember the exceptions, it works. The same is true for the extended alphabet mnemonics. The order of treatment expressed by X-ABC and MARCH works well for tactical situations and is easy for soldiers to remember, but it shares the same exceptions as the ABC alphabet mnemonics. Is WMTC's 3-triangle image mnemonic better? We think so because its ordered but non-linear structure encourages critical thinking and adapts to real-life scenarios and new research better than an entirely linear system. Will it work better for you? Take a course from us, and you decide! Ultimately, the best mnemonic is the one you can remember and use. 1 (2010). 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science. Circulation, 122(18).

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed