|

Human health is linked to the health of the environment, including its plants and animals (yes, insects are classified as animals: Kingdom Animalia > phylum Arthropoda). Infectious diseases in humans are caused by viruses, bacteria, parasites, or fungi, and transmission is via one of four routes:

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

0 Comments

Fleas, mosquitoes, lice, assassin bugs, sand flies, chiggers, ticks and other biting insects may be carriers of an infectious disease. With the advent of global warming, insects and insect-borne infectious diseases are spreading to new areas. To protect yourself against contracting an insect-borne infectious disease, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends using the following insect repellents and insecticides; they have been shown to be safe and effective, even in pregnant and breastfeeding women. Clothing, tents, and mosquito netting are ideal for first order of protection and sleeping, especially when saturated with Permethrin (which kills insects on contact). To protect against chiggers and ticks, wear light-colored or white long pants, long-sleeved shirts, and socks so ticks can be more easily seen; pull socks over pant cuffs. Wear a hat and place petroleum jelly around hairline to keep ticks from crawling into hair (where they will be very difficult to find). Do a thorough tick check each morning & evening before entering and leaving your tent. The CDC does not recommend other insect repellents and products as they have not been shown to be effective despite manufacturers claims. These include natural plant oils, (such as citronella oil, cedar oil, geranium oil (or geraniol), and lemongrass oil), repellents containing vitamin B1 or garlic, and wristbands and ultrasonic devices. Application

DEET

Picaridin

IR3535

Lemon Eucalyptus Oil

Permethrin

Interested in learning first aid? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. At times, the evacuation of a patient may be necessary for their further assessment, definitive treatment, and/or simply additional recovery time. All evacuations in a wilderness environment carry some inherent risk to members of the rescue party and the decision to evacuate a patient should NOT be taken lightly. The need for evacuation depends on the severity of the patient’s injury or illness and your resources. The type of evacuation depends on the mobility of the patient, the size of your party and its resources, the difficulty of terrain, the weather and the distance involved. Any evacuation, regardless of the type—self, assisted, simple carry, litter, vehicle—should not endanger either you or your patient beyond your capacity to deal effectively with the risk presented during the evacuation. In most cases, your field treatment for minor non life-threatening injuries will be effective and rapid evacuation will not be necessary. By contrast, your field treatment for most life threatening illnesses or injuries may simply buy you and your patient some time. In these situations, focus on a quick accurate assessment and fast evacuation. The “medical window” for life-threatening problems is often specific to the particular illness or injury. If an emergency evacuation is not possible, your field treatment will usually be limited to treating the patient’s signs & symptoms and supporting their critical systems; this is often ineffective and your patient may die. In general, any problem that causes a change in the patient’s level of consciousness is very serious. If a patient reaches definitive medical care (major hospital) while they are still awake they have a reasonable chance for complete recovery. If they reach definitive care with a significantly decreased level of consciousness (voice responsive, pain responsive, or unresponsive) their chances for a complete recovery, or a recovery at all are respectively reduced. In today’s world of rapid communication via cell or satellite phones, it may be possible to consult with medical or rescue professionals prior to initiating an evacuation. This type of consult should be encouraged and part of any emergency action plan (EAP). When in doubt, it’s always better to seek a consult sooner rather than later. A thorough patient assessment is required prior to any medical consult and the use of a detailed patient SOAP note will facilitate both accurate patient assessment and communication. At minimum, your location (GPS coordinates), party resources, and the current weather are required for a rescue consult. Conserve your batteries and set a communication schedule prior to signing off. When you are uncertain if a evacuation is necessary and a consult is unavailable, the following general evacuation guideline may be useful: any problem that is persistent, uncomfortable, is not relieved by your treatment—or cannot be effectively treated in the field—requires an evacuation. The speed of the evacuation depends on the degree of involvement, or potential involvement, of any critical system(s). The greater the degree or potential, the faster the evacuation. The following definitions for levels of evacuation are correlated to the severity of the patient’s injury or illness and hence the urgency and speed of their evacuation. Every effort should be made to accurately diagnose the patient’s current and anticipated problems since an incorrect diagnosis may lead to a false sense of urgency and a willingness on the part of the rescuers to accept more risk than the situation warrants. In general, rescuers should ONLY be willing to accept a level of risk they believe they can safely manage based on their skill and the foreseeable problems. Unfortunately, not all problems are foreseeable and the amount of risk any given rescuer is willing to accept tends to rise with the severity of the patient’s injury or illness. Since it is impossible to legislate judgment, rescuers, when in doubt, must base their decisions on the “worst realistic case” situation both in diagnosing the patient and evaluating the risk associated with the evacuation. That said, the risk of a minor injury or illness to a rescuer is generally present during most evacuations and unavoidable under the circumstances. WMTC Urgent Evacuation Levels Level 1 The patient’s injury or illness is immediately life threatening and the patient may die without rapid hospital intervention, e.g.: increased ICP, volume shock, severe respiratory distress, respiratory distress in a near drowning patient, advanced disease, moderate to severe hypothermia, HAPE/HACE etc. All VPU patients require a Level 1 Evacuation. Level 2 The patient’s injury or illness is potentially life threatening or will result in a permanent disability; the patient may develop a life threatening problem that requires hospital intervention, e.g.: concussion that is getting worse, systemic infection, spine & cord injuries, near drowning (no respiratory distress), etc. WMTC Non-urgent Evacuation Levels Level 3 The patient’s injury or illness is NOT life threatening, has little or no potential to become life threatening, and may be successfully treated in the field with no permanent disability; however, the patient is unable to resume normal activity within a reasonable length of time and/or requires advanced assessment. (E.g.: concussion that is getting better, unstable injuries with good CSM, reduced shoulder (dislocation) with good CSM, etc.) Level 4 (no evacuation) The patient’s injury or illness is NOT life threatening, may be successfully treated in the field with no permanent disability, and the patient is able to resume normal activity within a reasonable length of time, e.g.: minor wounds, minor stable injuries, minor environmental injuries, etc. There is typically little or no difference in the how a urgent evacuation is conducted. The difference lies in the mental preparedness and realistic expectations of the rescuers. If rescuers are not prepared for a patient death—as in a Level 1 Evacuation—research has shown that they will likely require more time to recover from post traumatic stress (PTSD) than those who recognize and accept that a patient’s death is a real possibility. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

For the purpose of this document “Wilderness Protocols” are defined as any protocols outside the traditional EMS curriculum but supported by practice guidelines published by the Wilderness Medical Society (WMS), the National Association of EMS Physicians (NAEMSP), and the American Heart Association (AHA), and the Scope of Practice documents published by the Wilderness Medicine Education Collaborative (WMEC). They will likely include but are not limited to:

In conjunction with their physician advisor, each institution should establish written wilderness medicine protocols to act as guidelines for the field management of trauma, environmental, and medical problems. The protocols should define when they should be used based on the timeliness of conventional EMS response. Wilderness Medicine Protocols are usually in effect when a group is longer than one hour from definitive care (with the exception of immediately life-threatening situations: e.g.: severe asthma, anaphylaxis, etc.) Institutions should also develop a first aid kit designed to support their guidelines and staff should be trained in the use of the kit contents on a regular basis. The use of weatherproof Patient SOAP Notes for documentation is highly encouraged. We recommend that institutions and their physician advisors review the NAEMSP position papers, WMS practice guidelines, and the WMEC Scope of Practice Documents before amending them to the needs of their program(s). Institutions should consider adopting the following general guidelines for staff trained to the Wilderness First Responder Level (WFR):

Authorization should be in the form of a written document that clearly identifies:

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.  Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and cardiocerebrial resuscitation (CCR) are valuable first aid skills and we should all master them. That said, their effectiveness is severely limited in a wilderness environment. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation uses a combination of chest compressions and rescue breathing to delay brain death and extend the resuscitation window while cardiocerebral resuscitation utilizes chest compressions only; both are potentially life-saving techniques. It takes approximately 10-12 chest compressions to build enough intrathoracic pressure to start circulating blood. The same intrathoracic pressure that circulates the patient’s blood also brings in a small amount of fresh air and oxygen. If there is residual air and oxygen in the lungs—as occurs in cardiac arrest caused by a heart attack—chest compressions alone are more effective in delaying the onset of brain death than when combined with rescue breathing because they maintain a consistent intrathoracic pressure. Conversely, a combination of chest compressions and rescue breathing (CPR) is more effective than CCR for patients whose arrest stems from a primary respiratory problem and lack of available oxygen as occurs in near drowning, lightning, complete snow burial, etc. The effect of both techniques decreases rapidly over time and cannot save or prolong the life of a pulseless patient for greater than 20 minutes and neither CPR or CCR work with major trauma patients whose arrest stems from increased ICP, significant lung damage, or volume shock. For CPR or CCR to be effective the patient’s circulatory system must be intact and their core temperature above 90º F (32º C); your chest compressions must be hard and fast (ideally at least 100 per minute) and delivered in the lower third of the patient’s sternum; your weight must be directly over the patient and the patient’s chest must be allowed to fully recoil between compressions; the recoil is as important as the compression. If rescue breathing is indicated, ventilate until the patient’s chest begins to rise; do not over-inflate—over-inflation forces air into the patient’s stomach and increases the chance or frequency of vomiting. In settings where rapid defibrillation, advanced cardiac life support, and rapid transport to a major hospital are not possible, the overwhelming majority of patients in cardiac arrest will die. It is important that all rescuers understand the limits of CPR and CCR and when it is appropriate to start and stop. When teaching chest compressions in our wilderness medicine courses we often tell students to compress at the rate of the beat in the Bee Gee's disco tune "Staying Alive" or Queen's "Another One Bites the Dust" depending on whether a student views the glass as half full or half empty.... (Yes, humor is important in the medical field.) Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

Introduction

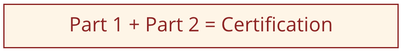

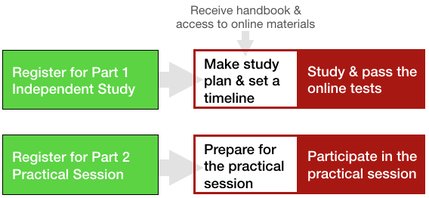

In 2007, we piloted our first hybrid course in wilderness medicine; in 2008 we opened them to the general public. Overall they were—and are—hugely successful. Our hybrid course curriculum is continually evaluated and our delivery systems updated annually. Each of our medical courses has a hybrid option. Your time and money are important; so is your education. We've written this article to explain—as thoroughly as possible—what you are getting into when you register for one of our hybrid courses. It's important to understand that the Wilderness Medicine Training Center International is both a business and an educational entity. We take our educational responsibility very seriously. That said, because our hybrid courses require a significant financial investment on our part to maintain and deliver, once you have registered and paid for a hybrid course there are no refunds. Please read this article carefully and contact our office if you have any questions before you register and pay for a course. Our hybrid courses are divided into two distinct parts, you must complete both parts within a year to receive certification.

Part 1

Independent Study Learn the wilderness medicine curriculum online and at your own pace through multimedia presentations, the Wilderness Medicine Handbook, case studies, SOAP Notes, and testing. The Independent Study section provides the foundation for the Practical Session and is presented entirely online with minimal or no instructor contact. Students can complete the Independent Study from wherever they can access the course website. The Independent Study section requires a high degree of initiative and self-direction. Students who prefer to learn completely under the direction of an instructor may be challenged to move through Independent Study effectively.

Part 2

Practical Session The Practical Session is facilitated by expert instructors who clarify and reinforce the Independent Study information with skill labs, simulations, and case study reviews. In cases when there is a significant time gap between the time you finish Part 1 and begin Part 2, you may want to take an online Review test before the start of your practical session. The review test is designed to refresh key concepts learned during the Independent Study. You can also review your original tests and you will still have access to the course website. You may register for for any Part 2 practical session offered by any WMTC sponsor after you complete the Part 1 Independent Study.

The Independent Study (Part 1) and the Practical Session (Part 2) both contain technical terminology as well as complex explanations of concepts. Students who are English language learners or who have certain learning challenges sometimes find this aspect of the curriculum difficult.

If you have questions about or difficulty deciding if a hybrid course is right for you, please contact our office before you register and pay for a course.

Part 1

Independent Study Details

Online Test Details

Practice Tests Practice tests are easier than the exams and may only be taken once. You will receive answers to the practice test questions immediately after submitting them, and while the test is scored, the score has no bearing on passing or failing the course. That said, your score will give you an idea of how well you understand the basic material. Exams The exam questions are scenario-based and and WFR, WAFA, and WEMT students need to score ≥ 80% to pass; WFA students must score 75% to pass. You will be able to study for, take, and retake each exam multiple times. (Some exams have a 2-4 hour mandatory study/waiting period before you can take the test again. We’ve found that students who take back-to-back tests without studying between them tend to fail the next test.) That said, there is a limit to the number of times you may retake a given exam. If you reach the exam limit, please contact the WMTC office. One of our senior instructors will review your last test, email you detailed written feedback, and give you one final opportunity to take that particular exam. You will have the opportunity to review the feedback and ask the instructor questions before taking the exam again. If you fail the same exam again, you may not continue with the course, attend the practical session, or receive a refund for the course. Keep in mind that historically 99% of the students who fail an exam, receive instructor feedback, and go on to take that exam again, have passed that exam. While we provide a time range for completing the Part 1 independent study portion of each course, it’s a rough estimate: You may require more or less time. It’s important that you plan and schedule more time than the high end of the estimate to help ensure you can complete the independent study portion in time to register for and attend a Part 2 practical session. Scoring Scoring for the online exams is complex as the answers are weighted: Correct answers are awarded 1-3 points while 0-3 points are subtracted for incorrect answers; the sum total is the score for that question, however, the lowest score anyone can receive for an individual question is 0 points. If you fail an exam, you are not given the answers or given an explanation; it's left up to you to research the exam question and answers using the course materials. This means that you cannot guess answers and will need to problem solve; details are important.

Hybrid Course Websites

The hybrid course websites are essentially an online textbook with text, animations, and videos. Because there is no direct instructor interaction during the independent study portion of the course (unless you fail an exam multiple times), the sites include case studies (and follow-up discussion) to check your understanding prior to taking the online exams. Keep in mind that the online exams are both an educational tool as well as an assessment tool. As such, they are challenging and few students pass on their first attempt. Please visit the hybrid course website you are interested in to see how it is organized and get a rough estimate of how much time you should plan in order to complete the independent study portion of the course; plan for more time than you think you will need. Thoroughly read the information on the home page and view the Lightning presentation to make sure the course meets your needs; the actual site is password protected, and entered via the button titled “Registered Students.” The website password together with login information to our online testing site and a link to the course study guide are sent to students upon registration. Hybrid Wilderness First Aid website Hybrid Wilderness Advanced First Aid website Hybrid Wilderness First Responder website Hybrid Wilderness EMT website Hybrid Recertification website

Part 2

Practical Session Details There are no formal lectures during the practical session. Instead, the practical session focuses on the practical application of the independent study information: skills labs (splinting, wound cleaning, reducing dislocations, assessing and managing potentially spine-injuried patients, etc.), simulations, and case study reviews in order to prepare you to respond effectively to real-life injuries and illnesses. The time you spend away from home or work is significantly less than that required by our standard courses. Many students can actually learn MORE via hybrid course because their they can absorb and process the information according to their learning style and at their own pace. Because there may be a large gap between the time you finish Part 1 and begin Part 2, you may want to take an online Review test before the start of your practical session. The review test is designed to refresh key concepts learned during the Independent Study. While the review test is scored so you can self-evaluate, there is no pass or fail;. however, you are responsible for knowing the information in order to pass Part 2 practical session. You will still have access to the course website and can look back through your original independent study tests to refresh your memory of key concepts.

Standard vs. Hybrid ~ Which one should I choose?

Both courses cover the same material using slightly different pedagogy. Tuition for both courses includes our weather-proof Wilderness Medicine Handbook and our Patient SOAP Notes. For some people, the primary decision-making factor is time away from home or work; for others, it has to do with their learning style, and still others it has to do with location or dates; for most, it's a combination. The tabbed information below should help you make a decision. Remember, you can always call our office and discuss the course type or format with one of our staff.

<

>

Factors when choosing a course sponsor and site:

Learn more about our pedagogy and delivery strategies. More thoughts on whether or not YOU should take a hybrid course If you like learning on your own, are intrinsically interested in wilderness medicine, have effective study habits, like problem solving, have enough time to study, have access to internet and a computer or tablet, (smartphones do work, but the screens are often too small) and would like to spend as little time away from home or work as possible, consider taking one of our hybrid wilderness medicine courses. If you are seeking to recertify your current WAFA, WFR, or WEMT certification, our hybrid Recertification course is a great option. As a graduate of an approved WAFA, WFR, or WEMT course, you already have a grasp of the didactic information and you could easily review lecture material on your own. Our hybrid WFR & WEMT Recertification course allows you to spend only the you need to brush up on your anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology by using the Recertification website, case studies, and the online exam to focus your study. You maximize the your time away from home practicing skills and participating in as many simulations and case study reviews as possible to refresh your skills. Graduates from other wilderness medicine schools should keep in mind that our courses may require a deeper understanding of anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology than your original course or use slightly different medical terminology. This may require more time to complete the independent study portion of the course than is estimated. If your WFR or WEMT certification has expired or you are looking for a more in-depth practice than a Recertification course can provide, our hybrid WFR or WEMT course may meet your needs. Similar to students seeking normal recertification, you already have a grasp of the didactic material and can review the basic lectures on your own. This is a great option if you need to brush up on your skills, renew your certification, deepen you knowledge of wilderness medicine, and maximize your time spent away from home and work. If you are a current EMT or medical professional seeking knowledge and certification in wilderness medicine you already have a working knowledge of normal anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology you'll appreciate our hybrid WEMT module. While the practice of medicine in a wilderness setting is MUCH different than its urban counterpart, your background and experience will likely allow you to rapidly move through the independent study portion of the course and, as mentioned above, maximize your time spent away from home and work.

There are people who should NOT take one of our hybrid courses.

Are you one of them? Our hybrid courses don't work for everyone. There are some people who should carefully consider the factors below before registering for the Part 1 Independent study portion of one of hybrid courses. Think twice about taking a hybrid course if:

Once you register for Part 1 or Part 2 of a hybrid course, there are no refunds. If you are unsure if a hybrid course is right for you, please contact our office for more information.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

This is an excellent practical question! Since students remember the skills and information they use on a regular basis, skill retention is shared by the wilderness medicine provider, their employer(s), and the graduate.

1. Wilderness medicine providers are responsible for:

2. Employers of wilderness medicine graduates are responsible for:

3. Graduates are responsible for:

Follow-up questions include (and will be addressed in later blog articles):

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. I think everyone benefits from a basic understanding of how the body works and how to take care of it; after all, we've each got one. From this perspective, everyone should take our Wilderness First Responder course. Like everything else associated with education, you need an effective curriculum, well-written study and reference materials, realistic training supplies (first aid kits, an full-sized anatomical torso, a full-sized skeleton, litters, backboards, etc.) trained teachers, and, ideally, intrinsically motivated students. We supply everything but the last component.

Unfortunately, most people are busy and taking time to learn about their bodies and first aid falls pretty low on their "to do" list. Enter extrinsic motivation: college or professional credit, job requirement, being involved in—or hearing about—an accident or incident that "could have happened to you" and not knowing what to do, etc. Once extrinsic motivation enters the picture, it defines the course parameters. For example, if you want to be a trip leader for ________ college and they require a Wilderness First Aid course, then it's likely that you will take the course they sponsor or recommend. At the same time, it's doubtful that you will seek out and take a more intensive Wilderness First Responder course; after all, a WFR is longer, more expensive, and will require a greater investment on your part. See how complicated the answer is to this apparently simple question? Moving on.... One way of looking at the answer to the above question is rephrasing it to mean "what skills will I REALLY use on a trip?" Well, that too, depends.... If you are on a day hike in moderate terrain in a neutral environment with young healthy people and have cell phone coverage (and you bring a fully-charged phone), you probably don't need to know a whole lot of first aid or bring a much with you in terms of first aid supplies. You'll probably benefit from knowing how to—and carrying supplies to—prevent and treat blisters and treat minor wounds, headaches, and pain. If you are untrained and reading this article, you probably already have some idea how to do all this, along with what to carry: a few band-aids®, some water, mole skin® or tape, and ibuprofen. If it's more complicated than that, you can always call for help. Right? Maybe. The problem with this way of thinking lies in the variables. If the terrain is dangerous (lightning, avalanche, rock fall, big rapids, etc.) it's likely that an accident will be more serious and require more training and supplies than you have to address. If the environment is too hot, cold, wet, dry, etc., you'll need more training, and perhaps more supplies to prevent (ideally) and treat (hopefully) any environmental problems that arise. If you have kids, older adults, or people with health issues, you may not have the knowledge or supplies to help them. What about the unexpected? What happens if someone gets stung by a bee, has a life-threatening allergic reaction, can't breathe, and you don't know how to treat them or don't have the materials (epinephrine auto-injector)? They will likely die before help arrives. I guess this might extrinsically motivate you to take a course but it won't help your friend.... The bottom line is that you don't know what you don't know. We have spent years and years as guides, outdoor instructors, rescue team members, and wilderness medicine instructors. We work very hard to develop a curriculum, delivery methods, materials, and instructor training program that remains unparalleled in the industry. And, we continue to research and improve every day. Take a tour of our website. Look at our individual medical courses and materials, think about our mission, vision and educational philosophy, take a look at the faces and experience of our instructors, visit our online store and see how our curriculum influences the design of our first aid packs, first aid kits, and the supplies we sell, and then come take a course from us. If you are interested in your wilderness medicine education, you'll be happy you did. Okay. So what course should I take?

There are a lot of wilderness medicine providers. Does everyone teach the same course? In other words, does it matter who I take a course from as long as I take one?

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Okay, winter IS cold. That's why we call it winter. Cold injuries—hypothermia, frostnip, frostbite, chilblains—are all potential problems. Fortunately with a bit of thought and practice, it's possible to stay warm, even in extreme cold. If you are a seasoned winter traveler, you're probably familiar with everything listed here. If you are new to playing outside in the winter, I trust you'll find a few things of value.

Children are physiologically and psychologically different from adults. You must take these differences into account, and act accordingly, when you bring your children into the outdoors. Below are a few things to think about before you head outside with kids.

Small children live completely in the present and are easily distracted; this makes it difficult for them to remember and follow the new and unfamiliar rules that accompany outdoor activities. In addition, the hazards presented by outdoor living and adventure sports are different than those most children are accustomed to. Young children and children new to a specific outdoor activity must be closely monitored at all times. When you decide to bring a child into the outdoors, the trip must focus on the child's needs rather than your own; get your enjoyment by watching them explore, grow, and have fun. Keep in mind that children are individuals and will not respond in the same way physiologically and psychologically. Common problems and solutions are discussed according to their mechanism below. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed