|

Contrary to how it is often depicted in movies, the act of drowning often goes unnoticed. There appear to be three separate actions or body positions people adopt when confronted with the possibility of drowning. Depending on their swimming ability, injuries, or illnesses, some will progress through all three of these stages, while others will not.

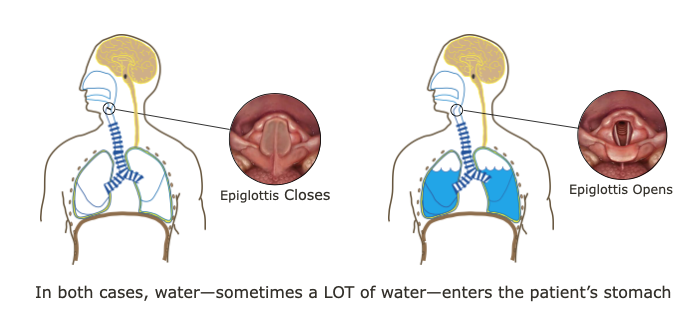

In a drowning, the victim is submerged under or immersed in water and requires rescue or assistance; not all drowning victims are unresponsive during their rescue and upon recovery, some are awake, voice responsive, or pain responsive. Drowning is a process with three possible outcomes: 1. Death, 2. survival with brain damage, and 3. survival without brain damage. In rare cases, primarily associated with cold water and young children, a few pulseless and apneic victims may also have a complete recovery if rescued within 30-90 minutes—depending on water temperature—and CPR started immediately. These fortunate few will have experienced an immediate shell/core response from core hypothermia or a phenomenon known as the "Mammalian Diving Response" or MDR. Many, but not all, drowning victims will quickly become unresponsive due to a systemic loss of oxygen and minutes later their heart will stop; in most cases, after roughly five more minutes they will suffer permanent brain damage. If not rescued, all unresponsive drowning victims will die. If rescued, the unresponsive patient who still has a pulse (but is not breathing) has a reasonable chance for recovery if rescue breathing is begun immediately. A patient who has no pulse and no respirations may, with immediate CPR, also recover completely, however, mortality is high. Given the potential for core hypothermia or an MDR, start CPR on all pulseless and apneic drowning victims who have been submerged for less than 30 minutes in water warmer than 43ºF (6ºC) or less than 90 minutes in colder water. If a recovery occurs during CPR, it will usually happen within the first few minutes. If pulse and respirations are not forthcoming, continue resuscitation efforts for a full 30 minutes. Click to read an article on cold water immersion. Most drowning victims aspirate very little water because their epiglottis closes and they swallow; the water, sometimes a LOT of water, enters their stomach. The majority of non-fatal drowning patients asperate less than 30 ml (1 oz) of water while fatal drowning patients aspirate 1-2 ml of water per kg of body weight (as found during autopsy). The aspirated water is absorbed into the microvascular bed surrounding the alveoli where it may wash out leading to alveolar collapse and cause an inflammatory response that leads to pulmonary edema (PE). In most cases, the S/Sx of PE will appear within 2-3 hours and non-fatal drowning patients should be monitored for 4-6 hours. Listening with a stethoscope—and occasionally with an ear to the patient's bare chest—will reveal rales, crackling noises that indicate fluid is accumulating in the patient's lungs. Foam in the patient's upper airway—or issuing from their mouth or nose—is the result of plasma (PE) mixing with the displaced surfactant. Decreased water quality increases the likelihood of pulmonary edema and subsequent respiratory infections. The amount of central nervous system damage (due to lack of oxygen and corresponding acidosis) will determine the patient's ultimate outcome. If the period of ischemia is limited or the victim rapidly develops core hypothermia (or an MDR) the damage may be limited and the patient may recover with only minor neurologic sequelae. The incidence of pulmonary edema increases with the amount of particulate matter dissolved or suspended in the water (e.g., salt, dirt, sand, chemicals, etc.). If CPR or rescue breathing is successful, a patient, even awake patients, may still die from pulmonary edema; if S/Sx of respiratory distress are present they may decompensate within the following 4-6 hours and death may follow within 72 hours. Delayed infection is also a potential respiratory complication that may eventually cause an pneumonia due to bacteria in the aspirated water.

Post-Resuscitation Assessment & Treatment

Want more information on this and other wilderness medicine topics? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available. Download the Wilderness Medical Society's 2016 Practice Guidelines for Drowning

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed