|

Boaters go out in all kinds of weather. Each year numerous people die by falling into cold water or capsizing their small boats; some die quickly due to drowning, others more slowly from hypothermia. Some are on their own trips; others on guided trips. All are typically unprepared. Pathophysiology Water cools the body 25-30 times faster than air. Cooling occurs faster if the water is moving, as happens when a victim is immersed in current, whitewater, or waves, and even faster if the victim is swimming or struggling. Photo 1 shows heat loss from a body in the air; photo 2 shows heat loss from the core when an immersion victim remains motionless in cold water; photo 3 shows heat loss from the extremities while swimming cold water. Muscle tissue produces heat even at rest; during heavy exercise heat production increases more than ten-fold. The more insulation—clothing and/or fat—a victim has, the slower they cool. The rate of cooling is also proportional the victim's surface to mass ratio. Large, fat people cool significantly slower than small, thin people; adults cool slower than children. When a person is suddenly immersed in cold water, nerve endings in their skin stimulate peripheral vasoconstriction and sharp spikes in both their pulse and blood pressure. This increases their need for oxygen causing them to gasp for air; if their head is under water, they may inhale water and drown. This immediate response to cold water immersion also makes it difficult for the victim to hold their breath…and if upside down in a kayak or C-1 to successfully roll their boat upright. The initial gasp for air is quickly followed by hyperventilation making it challenging for the victim to breathe if immersed in whitewater or waves. If the victim has a preexisting heart problem, the increased workload on their heart may cause it to arrest. The initial shock of quickly and unexpectedly being immersed in cold water lasts roughly two minutes and is followed by a period of increasing functional disability as vasoconstriction continues to shunt blood to the victim's core and the muscles in their extremities continue to cool. Muscle cells function best at 104º F (40º C). Cooling alters nerve and muscle function sharply decreasing both strength and endurance, limiting the victim's ability to self-rescue. As their core temperature reaches 96º F (35.5º C), the victim starts to shiver. Severe shivering begins with the true onset of mild hypothermia at core temperatures around 95º F (35º C). Similar to moderate exercise, severe shivering increases heat production up to five-fold; however, it also decreases muscular coordination and impairs physical performance, further reducing their ability to self-rescue. Given limited insulation and no life jacket, most immersion victims have roughly two to fifteen minutes to self-rescue before they can no longer swim or hold on to their boat (or other floating object); due the added insulation and the ability to rest, wearing a life-jacket can double an individual victim's time to self-rescue. In most healthy people it takes 20-30 minutes to become mildly hypothermic. Shivering eventually stops as the victim's available calorie stores become depleted or the hypothalamus shuts down. Somewhere between 89º F (31.6º C) and 91º F ( 32.8º C) the victim's mental status drops, they are no longer able to support their head, and at this point they will drown if not wearing a life-jacket. Below 90ºF (32º C) the victim's heart becomes electrically unstable and increasingly predisposed to ventricular fibrillation (spontaneous cardiac arrest). If the victim is wearing a life-jacket and their head is out of the water, death due to immersion hypothermia—rather than drowning—typically takes at least an hour, even in ice water. Effective prevention and rescue begin with a realistic assessment of the hazards associated with with cold water immersion and how to mitigate them. You must consider the following five components:

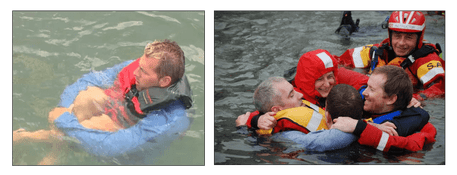

Insulation Proper clothing is vital to survival in cold water. There are two basic choices: wetsuits and drysuits. Wetsuits work by allowing the body to heat a thin layer of water between the victim's skin and the suit. They are awkward to paddle or work in but offer protection even when torn. A well layered drysuit offers more thermal protection—and is significantly more expensive—than a wetsuit. Drysuits keep water out. More expensive drysuits permit some water vapor to escape through the suit material and are typically more comfortable when paddling or working. Drysuits with booties are more comfortable than those without (wear socks underneath and wetsuit booties over top). Primarily due to a combination of expense and comfort, professional guides often choose to purchase and wear drysuits while their clients are typically issued wetsuits. It's vital for closed boat paddlers (kayakers and C-1 paddlers) to wear a helmet liner or neoprene (wetsuit) hood to reduce the cold chock phenomenon and give them time to execute a roll. Kayakers and C-1 paddlers sometimes wear a Farmer John wetsuit with a drytop rather than a full wetsuit or dry suit. Cold water survival suits are usually reserved for those working on boats in open water storm conditions where they run the risk of being washed overboard or the vessel runs the risk of capsize, and for rescuers preparing for and engaged in in-water rescue. Life Jacket In addition to adding insulation, a foam (vs. inflatable) life jacket adds enough buoyancy to keep an alert victim's head above water. Life jackets are sized to individuals and should be worn while on the water (not kept in the boat). Children should wear crotch-straps to prevent their life jacket from riding up above their head while in the water. Paddling Skills It's vital for paddlers to assess their paddling skills in light of the conditions (wind, waves, whitewater, etc.) to ensure that the trip they are planning to undertake is within their ability and estimate the likelihood of an unintentional swim. Swimming Ability Paddlers must also assess their swimming ability in the event of an unanticipated capsize under the current or potential conditions: whitewater, wind, waves, surf, current, etc. in the equipment they plan to wear. Self-rescue Skills Self-rescue skills, while closely related to the paddler's swimming ability, are also distinctly separate and should be both trained and practiced in rough water. Closed boat paddlers need to learn how to roll in adverse conditions. Sea kayakers need to learn how to re-enter and pump out a capsized kayak in rough water; whitewater paddlers need to learn how to swim themselves, and ideally their boats, and paddles to shore. SUP paddlers need to learn how to regain their board and paddle on their knees through rough water (surf, waves, or whitewater). Remember that without appropriate clothing and a life jacket the window for self-rescue is small. The obvious and pressing question for all paddlers who end up in the water is: "Should I stay with my capsized boat or swim for shore?" Corollary questions are: "Can I make it to shore?" "What happens if I don't?" Consider Assuming the proper clothing and life jacket, a whitewater paddler who capsizes and swims in a rapid, may need their boat for additional floatation until the rapid ends. At that point, if rescue is not eminent, they should consider swimming to shore with their boat and paddle. If towing the boat and swimming with their paddle will cause them to miss shore and enter a second, potentially dangerous rapid, they should abandon their gear and swim safely to shore. This decision must be made quickly and typically comes from a place of experience. No novice paddler should be this far from support/rescue. The same would hold true if the paddler did NOT have the proper clothing or life jacket. Assuming the proper clothing and life jacket, a paddler who capsizes in open water should stay with their craft if rescue is likely because the boat is easier that a swimmer for rescuers to see. If rescue is unlikely, they should consider swimming to shore, if that is an option. The decision changes if the paddler does not have the proper clothing. If they have a life jacket they can consider swimming to shore; if they don't make it, their life jacket will still keep them afloat in the event they are found. Without a life jacket they should stay with, and ideally on top of, their boat. With or without the proper clothing but wearing a life jacket, victims who find themselves in cold open water waiting for rescue should should reduce their surface area and conserve body heat by drawing their knees up to their chest if alone or huddling with others victims if in a group. Rescue Skills Rescue skills are separate from self-rescue skills and apply to helping others right and re-enter a capsized boat, tow a victim to shore, use a throw rope to recover swimmers from a difficult rapid, how to approach a swimmer safely, how to bring a pain or unresponsive victim into a rescue boat, etc. Rescue skills are specific to the environment and craft, and MUST be practiced to mastery in the actual conditions the rescuers are expected to operate in. First Aid Skills First aid skills different but closely related to rescue skills. It's vital for rescuers to understand how to package and treat both drowning and hypothermia. Heart Attack Victims with a pre-existing heart problems may have a heart attack upon immersion. Drowning It takes more than an hour for hypothermia to cause death by immersion in cold water...but cold water immersion victims can drown quickly, within a few minutes, if their head is underwater when they initially gasp for air or minutes later if they lose their their ability to swim and are not wearing a life jacket. In either case, they have NOT been in the water long enough to die from hypothermia. If after rescue, they are unresponsive without a pulse or respirations, begin immediate CPR. If their pulse and breathing return, begin an urgent evacuation to the nearest hospital. Even if the victim regains consciousness, they are a candidate for delayed pulmonary edema and should be immediately transported to the nearest hospital. Click to read an article on drowning. Moderate or Severe Hypothermia Remember that the hearts of hypothermic victims with a core temperature below 90º F (32.2º C) are electrically unstable. Patients who are found floating in a life jacket voice responsive or pain responsive MUST be handled very gently during and after rescue to avoid ventricular fibrillation (cardiac arrest). The same is true for those who are found floating unresponsive with their heads out of the water; even if you cannot find a pulse and they appear not to be breathing, they may still be alive. Carefully remove the patient from the water, remove their wet clothes, place them in a hypothermia package and transport them to a hospital. DO NOT attempt to exercise high voice responsive patients as this will circulate cold acidic blood from their extremities to the core and precipitate cardiac arrest. DO NOT attempt to externally rewarm any moderate or severely hypothermic patient in a sauna (or hot water) as this will cause rapid peripheral vasodilation, a rapid increase in heart rate and accompanying drop in blood pressure, and precipitate cardiac arrest. Want more information on this and other wilderness medicine topics? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed