|

Introduction Spending time outside for work or play is part of human history, both past and present. Interest in the outdoors is constantly growing with new human-powered and motorized activities/sports emerging on a regular basis. The development of more sophisticated equipment allows access to more challenging terrain and environments...and greater risk. Use permits, once unheard of, are now the rule—and are increasingly difficult to procure for both individuals and organizations. Wilderness ethics are changing as use increases and "leave no trace" has become a mantra for many. In short, the outdoors has become a thriving industry. Most traditional sports (football, baseball, soccer, golf, etc.) take place in a controlled environment, at a fixed site with known hazards (a sports field, court, mat, etc.), and in close proximity to medical assistance. In contrast, many outdoor activities occur in a potentially challenging and austere environment, where unexpected hazards can appear at any time, and where access to definitive medical care is typically delayed, sometimes for days. At any moment, trip leaders may be called upon to make on-the-spot decisions that directly affect the health and safety of those under their care. To be effective under these conditions, trip leaders require in-depth and often specialized training. As interest increases in camping, hunting, fishing, outdoor recreation, outdoor therapy, and outdoor education, there is also an increased need for effective outdoor leaders and guides. This is the first article in a three-part series that examines the training of outdoor leaders: where it is today and perhaps where it is going, or needs to go, in the future. Regardless of the type of outdoor activity, outdoor leadership skills can be broken down into four areas:

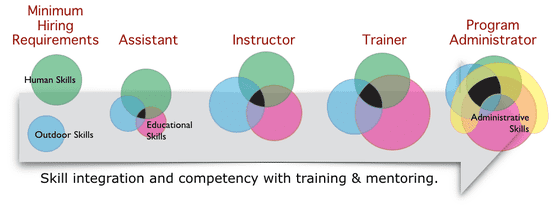

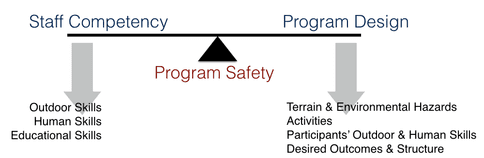

Outdoor skills include the activity-specific technical skills (climbing, sailing, paddling, skiing, etc.), equipment repair and maintenance skills, medical skills, hazard recognition, rescue skills, and site management skills a student must master before becoming an outdoor leader. Human skills include the ability of the student to accurately assess themselves and others (students, staff, parents, etc.) and the communication, coaching, counseling, and mentoring skills required to interact effectively with their students and co-workers. Educational skills include the ability of the trip leader to develop effective activity progressions and teach the required outdoor and human skills necessary for their students to manage the risk they encounter while on the trip or engaging in an outdoor activity. Each of the skills in each skill set must be taught, practiced, and assessed prior to working for an organization as a trip leader; and each are specific to the activity, environment, and organization. Most organizations hire entry-level staff based on their outdoor and human skills. In some cases, the educational skill set is ignored. In other cases—typically those associated with college and university undergraduate and graduate programs—the outdoor skills are ignored. More about this later. A typical trip leader skill progression is illustrated in the diagram below. A challenge in our current and still maturing outdoor industry is to create an operational language and training pathways to develop effective outdoor leaders and administrators. Unfortunately, while the human, educational, and administrative skill sets may be taught along traditional college and university pathways, the outdoor skill set must be taught off-campus—in the mountains, rivers, deserts, canyons, and oceans under the conditions where the trips/activities occur. Over the years, numerous grass root certification programs have emerged to fill the outdoor skills training gap with varying degrees of success. College and university undergraduate and graduate programs followed after many of the certificate programs became established as industry standards. Unfortunately many of the collegiate programs have no outdoor skill requirements and some certification programs are ineffective. Inherent & Actual Risk Different activities and environments have different levels of inherent risk associated with them. For instance, a backpacking trip on relatively smooth, well-marked trails in mild weather has less inherent risk than an off-trail backpacking trip, over rough terrain, in wind and rain (or extreme heat) which, in turn, has less inherent risk than a winter high-altitude mountaineering trip in avalanche terrain that includes technical mixed climbing on snow, ice, and rock. It's also worthy of note that the inherent risk in a new trip or one that includes a new activity or new environment is higher than that of an established trip. That the inherent risk is higher doesn't necessarily mean that the actual risk is higher. The actual risk of any program, trip, or activity depends on how the inherent risk and hazards are managed. How risk is—and hazards are—assessed and managed is one of the primary purposes of trip leader and administrator training and evaluation. Significant student injuries and deaths are rare in outdoor programs because most trips and activities have low inherent risk and those with higher inherent risk tend to be managed well. That said, serious injuries and deaths do occur. In my experience, they are usually the end result of a cascade of errors, a set of fallen dominoes where each domino represents a poor, often seemingly minor, decision. While initial errors can be made by program administrators, the "final" error is always made by the trip leader in the field. Training focuses on recognizing the potential decision points and how to make the "correct" decision, the one that interrupts and derails a potential cascade. With 20/20 hindsight many of these decision points are evident, but only if you take the time to look. Most programmatic near misses, injuries, and deaths can be traced back to a training and/or assessment error by the program administration. Certification & Degree Programs Certifications and degree programs are independent efforts to train and evaluate outdoor leaders. The ultimate purpose for both is to prepare students for employment by training them how to assess and manage risk and provide documentation of their outdoor, human, and educational skills. On the surface, this appears to be both logical and reasonable. What is unreasonable is to assume that because a student takes a course and receives certification, or a passing grade, for successfully completing that course, they have mastered the material. In the overwhelming majority of cases, this is a false assumption. It takes practice and mentoring to master most skills; this is especially true for the majority of outdoor skills. In addition, both skill mastery and retention require constant practice and on-going training. Employers, regardless of the industry or job, typically rely on a resume and Vita that includes recommendations, certifications, degrees, and experience to initially screen applicants. In this, the outdoor industry is no different; however, problems can arise when an employer relies solely on the paperwork and does not directly assess the applicant's skills in the field. This is especially true for applicants with undergraduate and graduate degrees that do not include documented field time and training logs. The Pros & Cons of Certifications Pros

The Pros & Cons of Undergraduate & Graduate Degree Programs Pros

In order to become an effective outdoor leader you will need to master the outdoor leadership skills required for your job. Currently you don't need a college degree to learn and master them—or to get a job—but you will need training, practice, mentoring, and at least a certification in wilderness medicine, typically a Wilderness First Responder; some jobs require additional certifications. To become an effective outdoor program administrator you will need to be an experienced outdoor trip leader and trainer and you will need a full administrative skill set. You can receive training in outdoor leadership skills—and in many cases certifications—from:

Pathways for Professional Trip Leaders Consider the following options or combination of options. While formal training can help speed skill mastery, you will need to spend a significant amount of time practicing on your own trips and expeditions.

Widely Accepted Certifying Bodies within the United States

Pathways for Administrators

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed