|

For over four decades and with little or no data to back it up, EMS fully immobilized all patients involved in major traumatic incidents in order to prevent neurological damage from a potential spine injury. The premise underlying this practice was that a major traumatic event could injure the patient's spine and subsequent spinal movement would result in a cord injury, and full external spinal immobilization would prevent said movement. This precept is seen as false and spine management in both urban and wilderness environments has changed—or is in the process of changing—accordingly. Read on to see how and why this transformation has taken place...and what the current spine management guidelines are for wilderness and remote locations. In 1998, Professor Mark Hauswald (Department of Emergency Medicine, University of New Mexico) released a five-year retrospective study comparing trauma patients in Malaysia with those seen in a US hospital. None of the 120 patients seen at the University of Malaya were immobilized during transport while all 334 patients seen at the University of New Mexico were. The study showed a significantly higher rate of neurologic injury in the immobilized group. The study brought current spine management guidelines into question and sparked decades of research. In 2012, Dr. Hauswald released another article on the biomechanics and pathophysiology of spinal injures that challenged existing spinal immobilization theory. In his article Dr. Hauswald asserts that most spinal injuries are biomechanically stable, that the majority of those few patients with unstable spinal injuries will already have spinal cord damage as a result of the forces imparted during the traumatic event, and that pre-hospital immobilization will not affect either patient's outcome. This means that cord and neurological injury can only be caused by a second traumatic event where new force is applied to the injured area, and movement within the patient's normal range of motion is safe. Increased research over past two decades—primarily due to Hauswald's work—has clearly shown that spinal immobilization:

Here's what else we know:

So how should we treat patients in a wilderness or remote locations? The treatment goal is to prevent a spinal cord injury. To that end: Assume a patient has a Spine Injury when the MOI is Trauma or Unknown and support all voice-resonsive, pain-responsive, and unresponsive patient’s spines during Basic Life Support. Ask awake patients to remain still as you check and treat for severe bleeding during your primary survey. Do not attempt to hold a patient’s head or restrain them, especially if they are anxious or combative. Begin the focused spine assessment (FSA) only after you have completed all three triangles of the Patient Assessment System to ensure the patient is reliable. Treatment Principles for Spine & Spinal Cord Injuries

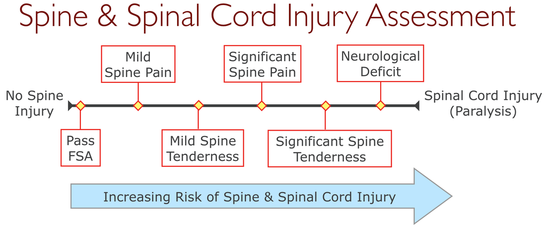

The Focused Spine Assessment (FSA) is very conservative: It's negative predictive value is roughly 99%. This means there is less than 1% chance a patient who passes the FSA actually has a spine injury. On the other hand, the FSA's positive predictive value is, at most, 4%. This mean that roughly 96% of the patient's who fail the FSA do not have a spine injury. The risk for an actual spine injury increases as spine pain and tenderness increase, and increases significantly further if neurological deficit is present; the exact amount, unfortunately, is unknown. When assessing whether a patient who fails the FSA should be permitted—or encouraged—to self-evacuate, you will need to consider the severity of their S/Sx (above), the difficulty of the evacuation (are they likely to fall and cause further damage), and the hazards of waiting for outside assistance. Additional Risk Considerations

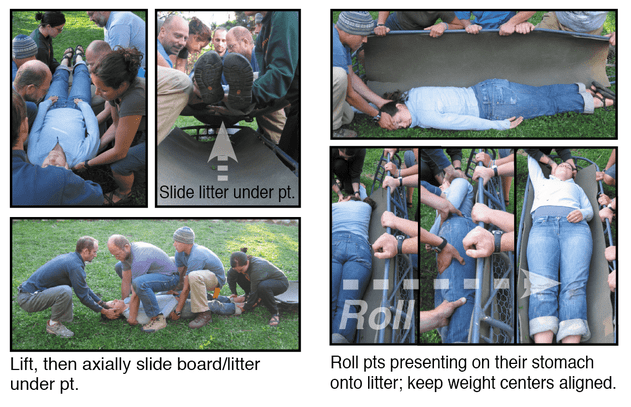

Lifting & Moving Guidelines for Voice-responsive, Pain-responsive, and U Patients

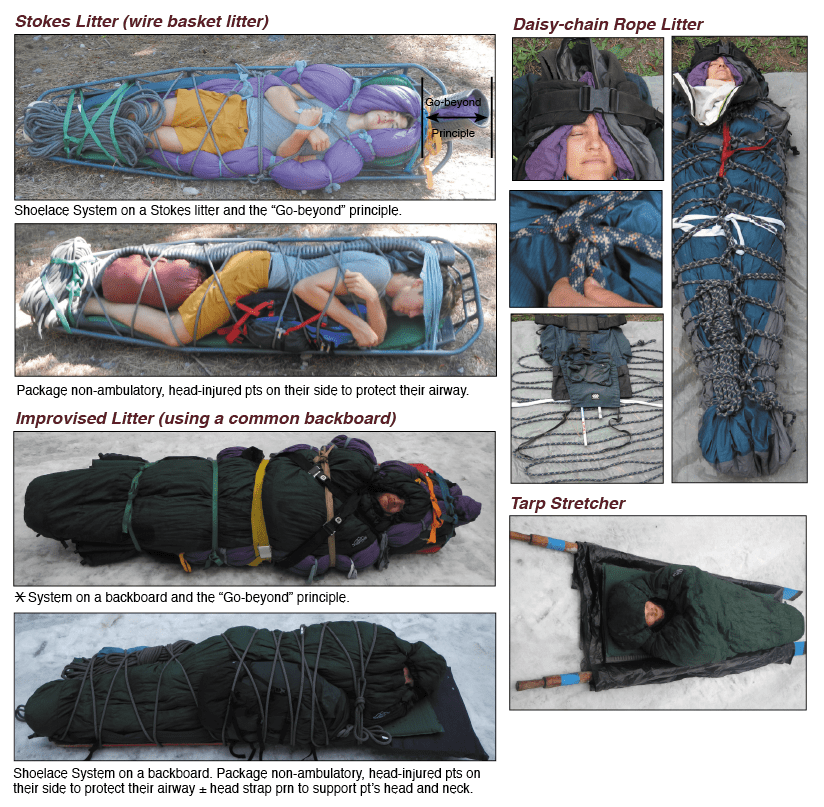

Litter Packaging Guidelines for Non-ambulatory Patients

Want more information on this and other wilderness medicine topics? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course.

Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

4 Comments

2/18/2020 07:17:52 am

If a patient has an unstable cervical injury, and ,as this article suggests, the head is not supported, albeit gently, and the patient exam locates an exquisitely painful ,but unseen injury, which causes severe movement due to pain, why would the gentle support of the head not avoid further damage to the cervical spine ?

Reply

12/24/2020 11:22:09 pm

I agree with you Bill, Thank you for putting this here.

Reply

Penny

4/22/2024 06:02:29 pm

I believe the issue here is not that gentle support of the head will not avoid further damage to the cervical spine, rather normal physiological motion will not cause further damage. The emphasis has become spinal motion restriction rather than full spinal immobilisation. Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed