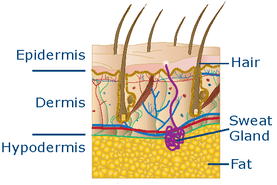

(How to avoid, and if necessary treat, dry, chapped, and cracked skin on an outdoor trip.) The skin is the largest organ of the body; it varies greatly in thickness offering both physical protection from minor traumatic injury and denying access to potentially dangerous microorganisms. The outer layer of the skin (epidermis) is extremely tough and contains melanin while the more sensitive underlying layers—dermis and subcutaneous tissue (or hypodermis)—contain blood vessels, nerve endings, subcutaneous fat, and connective tissue. The skin on your hands and feet is much thicker than the skin on the rest of your body, and therefore tougher; it can take up to six months for severely chapped hands and feet to heal sufficiently and regain its barrier strength. Aside from your lips (a notable and important exception), your skin contains melanin to help protect it from excessive ultraviolet (UV) radiation and has glands that excrete water, electrolytes, and oils. Blood vessels within the skin layers aid in thermoregulation as they contract to conserve heat or dilate to release it. Sensory nerves transmit environmental messages to the brain. Dry, chapped, and cracked lips, hands, or feet are, at the very least, uncomfortable and at worst, may lead to an infection and evacuation. Problems tend to arise as environmental conditions become increasingly dry, hot, cold, windy, and/or wet. Exactly the type of conditions found on many wilderness trips. Wind quickly draws heat and moisture from exposed skin. Cold causes vasoconstriction thus reducing blood flow to the extremities and slowing general cell maintenance and healing; cold skin cold skin is also more susceptible to trauma. Constant immersion in water breaks down the epidermis; long-term immersion in cold waster is especially dangerous as it can lead to trench foot. It's important to note that as people age, their skin becomes thinner and more susceptible to damage. Ultimately, how well your skin can withstand harsh conditions has a lot to do with your genes; some people are simply more susceptible to dry, chapped skin than others. Fortunately, with awareness, knowledge, and a the proper equipment and supplies, no one needs to suffer from dry, rough skin and painful cracks on an outdoor trip. Unfortunately, many people do. The first step is prevention and begins with recognizing the environmental conditions you may encounter on your trip or expedition. Come prepared and take preventive action well before dry skin becomes cracked. Protection begins with proper gear and by using a protective skin product on exposed skin. Much of this is "common" sense. Some requires education.

The second step is to apply a moisturizer multiple (5-6) times a day before your skin becomes dry. There are a LOT of moisturizer preparations available in drug stores and on the internet. Look for preparations that contain emollients and humectants; avoid those with fragrances or dyes. Emollients fill the crevices between skin cells that are ready to be shed and help the loose edges of the dead cells that are left behind stick together. They act as lubricants on the surface on the skin and make the skin feel slippery (not the best thing for technical paddling). Effective emollients include: lanolin, jojoba oil, isopropyl palmitate, propylene glycol linoleate, squalene, and glycerol stearate. Humectants draw moisture from the air to the skin's surface, increasing the water content of the epidermis. Common humectants are: glycerin, hyaluronic acid, sorbitol, propylene glycerol, urea, and arctic acid. In most cases, using the correct equipment, avoiding excessive hand-washing, and daily use of a moisturizer that contains both emollients and humectants will prevent your skin from drying. If you notice it isn't working, you need to take a more active roll to protect your skin from cracking; cracks are extremely painful and can lead to infection and, in severe cases, an evacuation. Essentially this means slathering on a heavy petroleum-based moisturizing ointment at night and wearing white cotton gloves or socks (to keep your clothing and sleeping bag clean). Plastic bags secured at the wrist (or ankle) can be used in place of gloves (or socks). In severe cases, the ointment can be used during the day under a light-weight (1/16-inch thick) pair of neoprene liner gloves or socks in winter or on cold water and light-weight, white cotton gloves in arid, desert environments. If you have chronic problems, see a dermatologist to rule out an exacerbating skin conditions like eczema or psoriasis. Should your skin develop painful cracks, use a cyanoacrylate pen (Super Glue, Krazy Glue, etc.) to glue the cracks together (preferably before they start to bleed) and treat as above. When on personal trips or acting as a guide in harsh conditions (shoulder season paddling and cycling trips, winter ski and climbing trips, and mid-season desert trips) I require everyone to:

In the group equipment I typically:

Want more information on this and other wilderness medicine topics? Take one of our wilderness medicine courses. Guides and expedition leaders should consider taking our Wilderness First Responder course. Looking for a reliable field reference? Consider consider purchasing one of our print or digital handbooks; our digital handbook apps are available in English, Spanish, and Japanese. Updates are free for life. A digital SOAP note app is also available.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Our public YouTube channel has educational and reference videos for many of the skills taught during our courses. Check it out!

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed